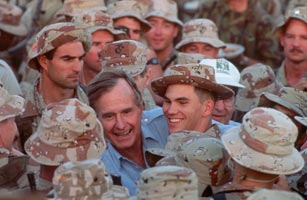

President George Bush shakes hands with US Army troops in Saudi Arabia during the Gulf War on Thanksgiving Day, 1990

(4 of 5)

The goals of American strategy were probably debated most thoroughly last Aug. 23 in an unlikely setting: aboard Fidelity, Bush's speedboat, bobbing off Kennebunkport. While Bush and National Security Adviser Scowcroft trolled for bluefish, they reviewed the U.S. experience four decades earlier in Korea, another "police action" fought with U.N. authorization. Scowcroft reminded Bush that soon after General Douglas MacArthur's bold victory at Inchon in September 1950, the U.S. succeeded in restoring the situation that existed before the outbreak of war by pushing Kim Il Sung's invading army back to the < 38th Parallel, the boundary dividing North and South Korea. The U.S., however, tried to unify Korea by driving all the way to the border with China. The result: Beijing intervened and drove American forces back almost as far as the old border. The conflict lasted nearly three more years, cost tens of thousands of additional U.S. and civilian casualties and poisoned U.S.-Chinese relations for 20 years. All to end up back at the status quo ante.

In the gulf crisis, Scowcroft warned, a war fought not only to liberate Kuwait but also to cripple Iraq could splinter the coalition that Bush had so masterfully assembled. It could trigger violent resentment by the Arab masses against the U.S. and the Arab regimes allied with it. And it could create a power vacuum that Syria and Iran might rush to fill.

Iraq's massive conventional and chemical arsenals and its fast-track nuclear-weapons program, Scowcroft argued, had to be contained. But that could best be done through a continuing embargo on weapons and weapons technology and by a security arrangement among the U.N., the U.S. and the Arab states. "The world was not willing to make war on Iraq for these reasons before the invasion of Kuwait," said Scowcroft, "and it is not clear why the U.S. and its allies should continue a war against Iraq after the liberation of Kuwait."

Shortly after this discussion, Bush and his top advisers decided to make clear to Saddam that he could withdraw from Kuwait and still save both his skin and his face. He could tell his people that the invasion had got the attention of Kuwait and forced it to negotiate Iraq's demands for access to ports and control of the Rumaila oil field, which runs under both Iraq and Kuwait. Once a decent interval had passed after Iraq's withdrawal, the U.S. would not object if Kuwait made concessions to Iraq. Also, the U.S. would press for progress on the Palestinian issue, and Saddam could claim whatever credit he liked.

This message was delivered both privately — through the diplomatic channels of the U.S. and its Arab allies — and publicly, most notably in Bush's Oct. 1 speech before the U.N. General Assembly.

Down to the Wire

With the Jan. 15 U.N. deadline only two weeks away, both Saddam and Bush face fateful decisions. So far, Saddam has shown no real interest in a peaceful withdrawal. He has reinforced the 100,000 Iraqi soldiers and 350 tanks deployed in Kuwait and southern Iraq in the days just after the invasion + with 410,000 more troops and 4,100 tanks. Bush's attempt to "go the last mile" for a peaceful settlement by inviting Iraq's Foreign Minister Tariq Aziz to the White House and dispatching Baker to Baghdad for a face-to-face talk with Saddam has degenerated into a dispute over when these meetings could take place.

Pressures are mounting on Bush to bring the crisis to a speedy conclusion. Not least of these are the economic hardships the crisis has exacted on Iraq's neighbors. And high oil prices are dragging down the economies of every country save the few that supply oil.

The calendar exerts a grim logic. In March, gulf temperatures begin to rise as high as 100 degrees F, threatening both soldiers and weapons. On March 17 the world's Muslims begin observing Ramadan; in mid-June the annual pilgrimage to Mecca begins. The Saudi government, already uneasy about the army of infidels on its soil, is unlikely to approve the launching of an offensive at either time.

Even domestic politics has become a factor. Democrats on Capitol Hill have grown increasingly critical of what they view as an ill-considered rush to war. Many are angered by the President's stubborn refusal to consult with them in advance of his most momentous decisions. Bush's doubling of the U.S. force stunned lawmakers, military and diplomatic experts and a large slice of the public. Georgia's Sam Nunn, chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, held public hearings at which a parade of former high-ranking intelligence, defense and foreign policy experts from both parties counseled a more patient course.

But the Administration has many reasons for not waiting to see if sanctions can wear down Saddam's resolve. One is the difficulty of holding the alliance together for the year or more it might take for the blockade to pinch harder. That will become even more difficult if, as Bush fears, Saddam announces a partial withdrawal from Kuwait that would leave him in possession of Bubiyan and Warba islands and the Rumaila oil field. With so little at stake, some allies — and some Americans — might no longer believe a war was worth fighting.