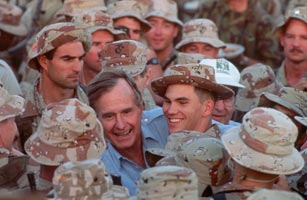

President George Bush shakes hands with US Army troops in Saudi Arabia during the Gulf War on Thanksgiving Day, 1990

(3 of 5)

From the earliest hours of the crisis, Bush worked to overcome those qualms. After his initial NSC meeting, he tried to phone King Fahd but failed to reach him. Bush then flew to Aspen, Colo., for a long-scheduled rendezvous with Britain's Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, who urged him to counter Iraq strongly. As the two leaders talked, Fahd returned Bush's call. The President told him, we think you are in danger. We are willing to offer air support and more. Fahd, in this and later conversations, expressed three concerns. If the U.S. sent troops to protect his kingdom, would the force remain until there was no longer a threat from Iraq? Once the threat was removed, would the U.S. withdraw its troops immediately? Finally, would the U.S. sell Saudi Arabia the advanced warplanes and other weapons it would need to defend itself? Bush's reply: yes, yes and yes.

In the capital on Aug. 3, Defense Secretary Dick Cheney and Colin Powell, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, put the hard sell on Prince Bandar bin Sultan, the brash, 41-year-old Saudi ambassador to Washington. Bandar, a U.S.-trained fighter pilot, was shown satellite photos of Iraqi armored divisions massing along the Saudi border as though poised for an assault on the oil fields near Dhahran, 175 miles away. Bandar called his uncle the King, and assured Bush that U.S. forces would be welcome in Saudi Arabia.

Within weeks, it was the Saudis who were putting a hard sell on the U.S. They were so alarmed by the growing Iraqi threat just over their border that Bandar and Prince Saud al Faisal, Saudi Arabia's Foreign Minister, urged the U.S. to kill Saddam, using any necessary means. The astonished Bush politely declined, then observed to aides afterward, "It sure is easy for other people to say what the U.S. ought to be doing to Iraq."

Bush recognized from the first that the Saudis would not accept U.S. troops unless other Arab states, the U.N. and the Soviet Union also supported action against Iraq, and he and his aides were working overtime to arrange that. They helped pass a U.N. resolution condemning Iraq within hours of the invasion. Secretary of State James Baker, who was traveling in the Soviet Union, stood with his counterpart in Moscow and issued a joint declaration demanding Iraq's withdrawal. Algeria, Egypt and Morocco publicly condemned Iraq for the invasion. And the Arab League, in an unprecedented show of resolve, followed suit.

Bush called a second NSC meeting for Friday, Aug. 3, and made clear that he had decided to dispatch forces to deter any attack on Saudi Arabia. Two days later, however, Bush expanded his goals to include the liberation of Kuwait, declaring, "This will not stand, this aggression against Kuwait."

Over the next 30 days, Bush would place 62 phone calls to government leaders and heads of state. He pressed Japan, Germany and wealthy Arab states to provide emergency assistance for Turkey, Egypt and Jordan, nations hit hard by the embargo on trading with Iraq. He called on Saudi Arabia and Venezuela to pump more oil to make up for the 4 million bbl. daily shortfall resulting from the blockade on Iraqi and Kuwaiti shipments.

But this whirlwind of diplomacy represented only half of Bush's strategy. The other half was to present Saddam with a stark choice: quit Kuwait or be driven out by military force. To that end, Bush set in motion the largest U.S. military deployment since Vietnam. It began five days after Saddam's invasion with the dispatch of 210,000 troops to Saudi Arabia, enough to deter an Iraqi onslaught.

Once Bush had vowed to liberate Kuwait, General Powell urged him to deploy a force so massive that if war became necessary, it could be fought all out and won quickly, unlike Vietnam. By November, Bush had authorized a doubling of the force to 430,000, giving him the capacity to go on the offensive if Saddam refused to meet the Jan. 15 deadline set by the U.N. for Iraq to quit Kuwait.

Bush also learned a valuable lesson from Jimmy Carter's obsession with the U.S. hostages seized by Iranian students in 1979. Determined not to repeat that mistake, Bush deliberately downplayed Saddam's holding of 3,000 Americans, some of whom were placed at key military installations as "human shields" against American attack. Bush repeatedly insisted that he would not be deterred from military action by the hostages' fate. In early December his stern stance produced results. Saddam released his captives, apparently convinced that his "foreign guests" would not forestall a U.S. offensive and that releasing them might reap a propaganda benefit.

Muddling the Message

Despite his virtuosity in welding the international alliance, Bush has stumbled in explaining his strategy to his countrymen. He has consistently and clearly spelled out four goals: complete Iraqi withdrawal, restoration of Kuwait's government, protection of American citizens abroad and creation of regional stability. But in explaining his strategy and tactics for attaining those goals, Bush has been halting, ineffective and less than candid. He has particularly left doubts about why the wealthiest allies are contributing so little to this crusade, about his sudden rush to use force if Iraq does not comply with the U.N.'s demands by Jan. 15, and about what sort of peaceful settlement, if any, the U.S. would accept with Iraq.

At times, Bush has likened Saddam to Hitler and claimed Iraq is on the brink of obtaining nuclear weapons. (The consensus of Bush's intelligence experts is that an Iraqi nuclear weapon is about five years away.) Such belligerent talk suggests that Bush, despite his public statements, would not be satisfied with an Iraqi retreat but would seek to destroy Saddam's ability to threaten his neighbors by obliterating his arsenal.