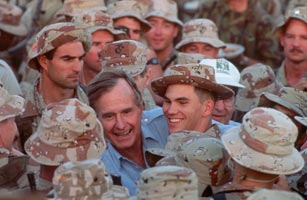

President George Bush shakes hands with US Army troops in Saudi Arabia during the Gulf War on Thanksgiving Day, 1990

(2 of 5)

Bush knew that only one power, the U.S., could thwart Saddam. The U.N. might pass a sheaf of resolutions, just as it has over the decades in trying to resolve the Arab-Israeli conflict, and with no more effect. As the Arabs and Israelis both like to say, dogs bark but the caravan passes.

Bush also knew, however, that Saddam had good reason for anticipating an ineffectual response. Only eight days before Saddam's army rumbled into Kuwait, U.S. Ambassador April Glaspie had told him, on instructions from the State Department, that Iraq's "border differences" with the tiny sheikdom were of no concern to the U.S. An outright takeover was another matter — but no U.S. official made that point to Saddam until after the fact. The American dog, Saddam assumed, would bark but never bite.

Bush, however, would prove him wrong. Against the initial judgment of many advisers, Bush was convinced that Saddam must be stopped now, before he became even more dangerous. Bush had been leafing through Martin Gilbert's The Second World War, and he cited Winston Churchill's view that World War II need not have been fought if Hitler had been thwarted in his 1936 push into the Rhineland, when he was weak enough to be deterred at relatively low cost.

Bush resolved that he, not Saddam, would shape the new world order emerging in the aftermath of the cold war. In this new order, the U.S. and the Soviet Union would work together through the U.N. to finally achieve the collective + security promised by the organization's founders in 1945. Bush thus found the "vision," at least in foreign policy, that he has long lacked.

Bush recognized that the U.S., as the last remaining superpower, must continue to lead, but with a different style. It must accommodate the rise of the economic giants Germany and Japan, and of various regional powers, while coaxing the Soviet Union, despite its retrenchment, to play a constructive role. America, Bush reasoned, must lead through painstaking and often frustrating coalition building — precisely the sort of personal diplomacy and horse trading at which he has excelled in the gulf crisis.

At first, Bush turned to the U.N. mainly to provide diplomatic cover for the Soviet Union and Saudi Arabia, as well as other Arab states reluctant to ally themselves with the "U.S. imperialists." But as the U.N. showed surprising backbone — first condemning Iraq's invasion of Kuwait, then imposing a stifling trade embargo and authorizing the use of military force to back it up — Bush grew ever more respectful of the organization.

As he implemented his developing vision, Bush, unlike Ronald Reagan, was no lone cowboy singlehandedly dispensing rough justice but a sheriff rounding up a posse of law-abiding nations. If his style is multilateral, however, it is anything but open. In the gulf crisis, as elsewhere, he zealously guarded his real intentions and game plan. All along he has retained tight control of virtually every detail of U.S. action, revealing as little as possible about his plans to the American people and to Congress.

That approach, however, could ultimately undermine Bush's policy in the gulf. The President's penchant for secrecy, his cunning stratagems, his willingness to commit the world's most powerful nation to a course that he alone determines, helped him assemble the alliance. But those very qualities engender doubts in the mind of many Americans, who have learned from Watergate and Vietnam not to invest too much faith in any one man.

Focus on the Saudis

In Paul Theroux's novella Doctor Slaughter, a young scholar at a dinner party observes that China's population has recently reached 1 billion. "Wrong," tut-tuts another guest, an international banker. "There are two people in China. And I know both of them."

George Bush could make the same claim. After the invasion, the intimate knowledge of world leaders and world politics that he had acquired during his years as ambassador to the U.N., envoy to Beijing and CIA director helped him forge an unprecedented international alliance. Throughout, Bush has displayed an exquisite sensitivity to diplomatic nuance and the need for subtle compromise — and sometimes outright bribes — required to bring together such mutually suspicious bedfellows as Syria, Israel, Iran and the Soviet Union. His performance went beyond competence to sheer mastery.

The initial focus of Bush's diplomatic offensive was Saudi Arabia. Though the kingdom feared it might be next to fall to Saddam's rapacious army, King Fahd had grave reservations about seeking U.S. protection. The King, Bush knew, was leery of accepting non-Muslim troops, whose presence might provoke unrest among deeply xenophobic elements of the Saudi clergy and people. He also could not afford to have the conflict portrayed as Iraq and the Arab masses vs. the wealthy monarchs of Kuwait and Saudi Arabia and their "Western imperialist defenders."