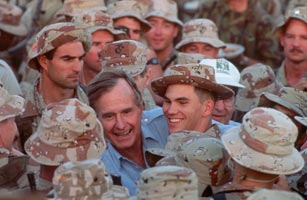

President George Bush shakes hands with US Army troops in Saudi Arabia during the Gulf War on Thanksgiving Day, 1990

(5 of 5)

In addition, a showdown postponed for a year or more would complicate Bush's 1992 campaign for re-election. Says an adviser to Bush: "We could have the economy in the toilet and the body bags coming home. If you're George Bush, you don't like that scenario."

Thus far, the greatest threat to the President's gulf policy has been posed not by Saddam but by one of Bush's long-standing weaknesses. He has found no voice to match his vision in the gulf.

While lavishing personal attention upon the foreign leaders in the anti-Iraq coalition, Bush has turned almost as an afterthought to the equally crucial task of convincing his countrymen that his course is just, his timing and strategy sound. He has brushed aside Congress's insistence that the Constitution empowers it alone to declare war. In private, Bush disdainfully insists he can ignore Congress as long as there is no consensus for or against his gulf policy.

History Lessons

In recent weeks Bush has spoken often of the "lessons of Vietnam." He means the military lessons: that if the U.S. goes to war, it must go to win, with overwhelming force instead of gradual escalation. A quick knockout would deprive critics of time to organize opposition, and the cheers of victory would drown out their protests. But the President has not digested an equally salient message from Vietnam: that the U.S. should not go to war without solid support from Congress and the people.

According to Scowcroft, the gulf crisis poses a crucial question: "Can the U.S. use force — even go to war — for carefully defined national interests, or do we have to have a moral crusade or a galvanizing event like Pearl Harbor?" Polls indicate that a majority of Americans support the use of force if Iraq will not leave Kuwait peacefully. But a large minority retain serious doubts. If war is necessary, there is little doubt that the U.S. and its allies will prevail. But it could prove a Pyrrhic victory if the cost in American lives is so high that it provokes a new wave of isolationism.

Bush's answer to the question he posed at the outset of the crisis — "What happens if we do nothing?" — was not to sit back and watch how events played out, as he had done so often before. It was to move, quickly and with great skill, to confront an act of aggression that might have set a disastrous precedent for the fragmented world that is emerging. His next moves could determine what future Presidents say when they gaze at his portrait on the White House wall.