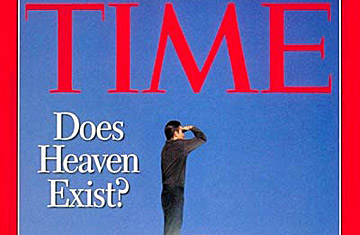

March 24, 1997 TIME Cover: Does Heaven Exist?

(4 of 6)

By the mid-19th century, however, heaven had hit a sort of ornamented bankruptcy. The stark vision of the Puritans had given way to what would later be called the Victorian heaven. Here was the humanistic heaven with a vengeance, calmly convinced of its own literal truth but with a spiritual core seemingly provided by House & Garden. Its strongest proponents were not clergy but a new breed of popular novelists like Elizabeth Stuart Phelps, whose 1868 The Gates Ajar, set in heaven, was a runaway best seller through the end of the century. Wrote Phelps of one celestial interlude: "We stopped before a small and quiet house built of curiously inlaid woods...So exquisite was the carving and coloring, that on a larger scale the effect might have interfered with the solidity of the building, but so modest were the proportions of this charming house, that its dignity was only enhanced by its delicacy ... There were flowers — not too many; birds; and I noticed a fine dog sunning himself upon the steps." There was dog, but there was very little God. The vision, like the age itself, honored human progress: it assumed almost all respectable people would reach heaven; if there were problems, they could continue working them out once they got there. The happiest prospect in this heaven was a slightly more idealized (and eternal) version of that already sugar-coated icon, the Victorian family. The model finessed the doubts about God that were seeping into the cultural mainstream by relegating God and even Christ into a nearly invisible role in the background. But it did so at a price. Without a compelling spiritual center, the vision of the future was hostage to the endurance of the society it mirrored.

Which meant that the 20th century blew it apart. Some indication of the shift can be had by studying the learning curve of Billy Graham. In his 1950 Boston revival, a young Graham was ebulliently specific about the world to come. Heaven, he said, was a place "as real as Los Angeles, London, Algiers or Boston." It was "1,600 miles long, 1,600 miles wide and 1,600 miles high." Once there, "we are going to sit around the fireplace and have parties, and the angels will wait on us, and we'll drive down the golden streets in a yellow Cadillac convertible." Graham went on to a magnificent career, but he dropped the Cadillac, which nonetheless haunted him for years. Late 20th century America had little patience for detailed, literal views of heaven. Two world wars and the prospect of nuclear disaster made the idea of a comfy, progressive afterlife seem suspect. Modernist attacks on God's place in this world made people allergic to bold predictions about his kingdom in the next.

By 1988, McDannell and Lang concluded their survey with the bleak assessment that "scientific, philosophical and theological skepticism has nullified the modern heaven and replaced it with teachings that are minimalist, meager and dry." Many scholars, especially conservatives, are inclined to agree. Kreeft, the Everything You Wanted to Know author and an old-style Catholic, says the cause lies in mainline religion's skittering away from strong faith statements and the notions of absolute morality. "Heaven," he says, "is uncomfortable because it's righteous and holy, not just fun." Agrees David Wells, the Evangelical: "Today the objective is to try to feel better about ourselves rather than to differentiate people morally. If you reduce salvation to our state of well-being, heaven doesn't make a lot of sense." Wells wonders about the perils of prosperity: "It's difficult for some people to conceive of anything that is really much better than this life. Sure, they go to bed appalled by the 11 o'clock news. But those buddies on the beer commercial saying 'It doesn't get much better than this' are speaking more deeply than they realize."

In the more liberal congregations, heaven is found mostly in hymns, preserved like a bug in amber. There are still some churches where one can find a robust heavenly vision in the late 1990s — among Southern Baptists, and African-American denominations as a whole. But most late-20th century American Christians, observes Jeffrey Burton Russell, have a better grasp of heaven's cliches than of its allures. "It's this place where you've got wings, you stand on a cloud, and if the concept is more sophisticated, where you see God and you sing hymns. It's a boring place, or a silly myth, or something people invent in order to make themselves feel better, or all of the above." Had Russell spoken these words a decade ago, it would surely have been in something close to despair. His tone today, however, can only be called cheerful.

So we do not lose heart...Because we look not to things that are seen but things that are unseen. —II Corinthians 4: 16, 18

It is hard to say whether there wasn't enough heaven in Russell's life or simply too much hell. Throughout the 1970s and '80s, Russell may have been America's foremost scholar of Satan, having published five acclaimed tomes with titles such as The Prince of Darkness and Mephistopheles: The Devil in the Modern World. But by the fall of 1987 he was suffering internal torment, compounded by a dreadful event in his personal life (a friend killed her son and then herself). "I was clinically depressed and spiritually in a very dark place," he says. "Fifteen years of studying evil was not an entirely healthy thing."

Then two things happened. He underwent psychotherapy and a course of the antidepressant Prozac. And his Italian publisher asked him whether he would be interested in writing a volume on heaven. Russell, who belongs to both Episcopal and Roman Catholic churches, notes that up until then, heaven "had been real for me. I had spent a lot of time thinking about moral choices, free will and salvation." But here was an invitation to a deeper immersion, culminating in a study of Dante Alighieri's 14th century epic Paradiso and its celebration of heaven as a "state of being in which we open up more to love." He accepted the assignment.