What would the world be, once bereft

Of wet and of wildness? Let them be left,

O let them be left, wildness and wet;

Long live the weeds and the wilderness yet.

-- "Inversnaid," by Gerard Manley Hopkins; Poems (1876-89)

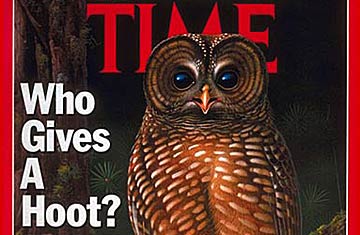

In Oregon's Umpqua National Forest, a lumberjack presses his snarling chain saw into the flesh of a Douglas fir that has held its place against wind and fire, rockslide and flood, for 200 years. The white pulpy fiber scatters in a plume beside him, and in 90 seconds, 4 ft. of searing steel have ripped through the thick bark, the thin film of living tissue and the growth rings spanning ages. With an excruciating groan, all 190 ft. of trunk and green spire crash to earth. When the cloud of detritus and needles settles, the ancient forest of the Pacific Northwest has retreated one more step. Tree by tree, acre by acre, it falls, and with it vanishes the habitat of innumerable creatures. None among these creatures is more vulnerable than the northern spotted owl, a bird so docile it will descend from the safety of its lofty bough to take a mouse from the hand of a man.

The futures of the owl and the ancient forest it inhabits have become entwined in a common struggle for survival. Man's appetite for timber threatens to consume much of the Pacific Northwest's remaining wilderness, an ecological frontier whose deep shadows and jagged profile are all that remain of the land as it was before the impact of man. But rescuing the owl and the timeless forest may mean barring the logging industry from many tracts of virgin timberland, and that would deliver a jarring economic blow to scores of timber-dependent communities across Washington, Oregon and Northern California. For generations, lumberjacks and millworkers there have relied on the seemingly endless bounty of the woodlands to sustain them and a way of life that is as rich a part of the American landscape as the forest itself. For many, all that may be coming to an end.

This week the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is expected to announce whether it will list the northern spotted owl as a threatened species. If the owl is listed, as many predict, the Government will be required by the Endangered Species Act to protect the bird. And if a preservation plan advocated by biologists is put into effect, it could be one of the most sweeping environmental actions ever undertaken. Federal and state agencies say the plan, fully carried out, would set aside an additional 3 million acres of forests. That would slash by more than one-third timber production on federal lands, which accounts for nearly 40% of the region's total harvest. The possible result: mill closings and cutbacks costing 30,000 jobs over the next decade. Real estate prices would tumble, and states and counties that depend on shares of the revenue from timber sales on federal land could see those funds plummet. Oregon would be hardest hit, losing hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue, wages and salaries, say state officials. By decade's end the plan could cost the U.S. Treasury $229 million in lost timber money each year.