(9 of 9)

The controversy offers the U.S. an opportunity to reassess the cost of past profligacy and salvage what remains of a treasured legacy of wildlife and ancient forest. Neither the owl nor the timbermen are served by further governmental inaction or sham solutions. What is gained by waiting until the last fir topples, the owl slips closer to extinction, or the mills finally retool or shut down because there are no more old-growth trees available? The lesson of the owl is not that environmental and economic concerns are incompatible, but that the longer society lacks the political courage to act, the harder it is to find a solution. After years of industry obstructionism and governmental acquiescence, the Forest Service is finally experimenting with requiring more selective harvesting of trees, rather than clear-cutting. But many environmentalists fear that such half measures will not preserve the forest ecosystem.

In a sense, everyone is to blame for the current dilemma. Says Jolene Unsoeld, a Congresswoman from Washington State: "It is the accumulated actions of all of us -- those of us who admire a beautiful wood-paneled wall, environmentalists who want their grandchildren to know the ancient forests, and those of us who come from generations of hardworking, hard-living loggers. We are all at fault, because all of us wanted the days of abundance to go on forever, but we didn't plan, and we didn't manage for that end."

Since most old-growth forests are on federal land, they belong not to an industry or a region but to the nation. The federal bureaucracies that manage them have too often operated under antiquated guidelines, framed when the forests seemed inexhaustible and man was oblivious to all but his own needs. Those agencies must reappraise their roles as custodians of the land and recognize the widest interests of the nation, not merely the most deeply vested. To place timber production above every other concern in this era of expanding environmental awareness is an abrogation of the public trust.

These are times of shifting societal values, from an appetite for natural resources to a concern for environmental quality, from the need for a strong defense to the reality of eased world tensions. Each shift brings dislocation and hardship. When revisions to the Clean Air Act pass Congress, the use of high-sulfur coal will be curbed, and thousands of West Virginia miners will lose their careers. And the scaling back of the defense budget could put thousands more on the unemployment line.

What is the Government's obligation to those workers and to the loggers of the Northwest? It would be impossibly costly for Congress to insure every citizen against the winds of change. But when scores of communities are imperiled, relief measures are necessary. In the case of the Northwest, the Federal Government should help retrain loggers and millworkers and provide towns with grants to spur economic diversification. Congress could also help sustain the Northwest's processing mills by passing legislation aimed at reducing raw-log exports.

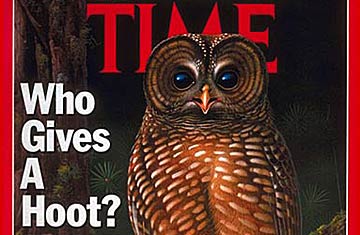

There is no way to avoid hard choices. The U.S. will have to recognize that no society can have it all at all times -- unfettered harvesting of natural resources, full employment and a healthy and rich environment. The soft hoot of the owl, an ancient symbol of wisdom and foresight, beckons us to resolve both its future and our own.