(7 of 9)

Fred Sohn, owner of Sun Studs, sees no difference between the reforested . stands and the ancient forest they replace. "I believe I as an individual can replicate the forest, redo it like a farmer growing a crop and do it better than nature," he says. "I can remake the old forest the same way nature did, only quicker." Talk like that riles environmentalists, who see the forest as more than just another fungible asset. Steve Erickson, whose father was in the timber industry and whose brother works in a mill, is writing a book about hiking trails. But Erickson finds it hard to share his vision of the forest. "It's like being in an artery in God's body," he says. Biologists and botanists speak in more scientific terms. They say the ancient forest is more than an aggregation of trees. To them the ancient forest's rotting trunks, decrepit firs and deep debris represent not waste, but vital nutrients in a vastly complex ecosystem.

Those who cut down the great firs may not see the forest that way, but many have no less reverence for it. The lumberjacks of Douglas County are not boisterous back-slapping rubes but pensive men who feel as much a part of this rugged landscape as the black-tailed deer and elk that retreat from the sound of their saws. A popular bumper sticker here declares, FOR A FORESTER, EVERY DAY IS EARTH DAY. Rather than surrender the name "environmentalist" to their foes, they have labeled the opposition "preservationists." Many loggers never finished high school but followed their fathers and grandfathers into the woods. They rise in the dark at 3 or 4 in the morning, pull up their suspenders and adjust rough hide pads on their left shoulders. The pads cradle the saws and, like trivets, shield the men from the hot blades that would burn their flesh through their flannel shirts. Their pants legs are tattered so that if they are suddenly snagged, the material will tear rather than hold. They do not wear steel-tipped shoes for fear that if a massive limb falls on their feet, it may turn the metal down and sever their toes. Better that their toes be crushed than pinched off.

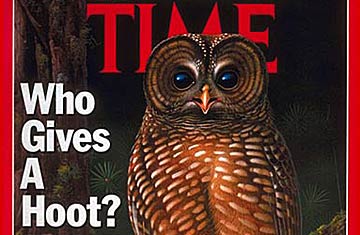

Few loggers or environmentalists have ever seen the elusive spotted owl. They know it as either a costly subject of litigation or a rare distillation of the forest spirit. But on the summit of a steep ravine in Douglas County, a pair of spotted owls assert themselves, as if to prove they are more than a mere abstraction. Nesting in the cavity of a broken-topped fir, they scan for prey and ponder the rare two-legged observer far below. Their gentle mewing ! gives way to a distinctive four-note hoot: "who-who, who-who." The male drops down for a closer look and settles on a limb 15 ft. from BLM biologist Oliver. "They have no fear of man," he says. In his hand, Oliver hides a mouse. The moment he exposes it, dangling it by its tail, the mouse disappears in a blur of wings and razor-sharp talons. The owl has carried it off and up to its mate, who snips off the mouse's head and ferries it skyward to the nest, where two snowy hatchlings devour it.