(3 of 9)

The life cycle of the Pacific Northwest's primeval woodlands is measured not in decades but in centuries. No amount of saplings and science can make up for years of wanton harvesting, or replace a thousand-year-old fir. Only time can do that -- and time may be short for those mills that are specially designed to devour the old firs. The owners eye the forests hungrily, knowing they cannot wait for the millions of seedlings and young trees to mature. If the industry is allowed to keep cutting, some forestry experts say, the last ancient forests outside wilderness areas could fall within 30 years. Thus many mills may be forced to close no matter what. Owl or no owl, the timber industry faces a painful conversion from its dependence on giant old-growth trunks to smaller trees in reforested stands.

Already the old growth has all but vanished from private lands. Most of the remaining great trees are in areas under federal control, administered primarily by the Forest Service. Many Americans believe these lands are all included in the national parks, and that the U.S. Forest Service is a gentle custodian of the woodlands. Except in certain protected wilderness areas, that is not so. The Forest Service and BLM, which oversee the public lands, are empowered to sell timber rights to the highest bidder, and sell they have -- a staggering 5 billion board feet a year, sweeping away 70,000 acres of old- growth forest annually. What is grown in its stead is not forest but "fiber," as the timber industry refers to wood.

One can grasp the distinction by looking out from any one of a thousand promontories in the Northwest. Clear-cutting -- the indiscriminate leveling of every tree in an area -- has left the wilderness fragmented and scarred. Long after the last truck has pulled out, heavy with logs, and the debris has been torched, what remains is a blackened earth, pockmarked and studded with tombstone-like stumps. "It looks like Alamogordo, as if it's been nuked," concedes Dan Schindler, a Forest Service district ranger.

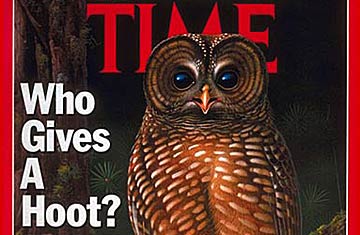

Though the timber industry has zealously replanted over the past two decades, the hallmark of old growth, biodiversity, has been lost. Gone are the broken-topped dead trees or "snags" favored by owl, osprey and pileated woodpecker. Gone the multilayered canopies and rich understory, the scattering of hemlock, incense cedar and sugar pine. Gone the centuries-old firs in their noble dotage. Increasingly, the forests have been transmogrified into tree farms of numbing uniformity, countless ankle-high seedlings and spindly saplings germinated from seeds selected for their productive capacity. The logging operations have tattered the seamless fabric of old growth that once covered the land. "There are more holes in the blanket than there is blanket," laments BLM biologist Frank Oliver. According to the National Audubon Society, each year enough old-growth trees are taken from the Pacific Northwest to fill a convoy of trucks 20,000 miles long.