(6 of 9)

Many who draw their living from timber concede that the owl is not their only problem. Jobs have been lost to automation too. A Forest Service study predicts that technological changes will displace 13% of the work force during the next 15 years. The recession of 1980-82 also took its toll. Export of logs overseas, particularly to Japan and China, has reduced the work available for local mills. And high production costs for lumber and plywood make the region vulnerable to competition from the South and Canada.

Burson knows the little owl draws attention away from these complex problems, some of which the industry brought upon itself. And he suspects industry is exploiting community fears for its own ends. "It's part of the corporate strategy to scare the hell out of us so we write letters and communicate with other people," says Burson. In a popular timber publication, industry lawyer Mark Rutzick wrote an article titled "You Have Enemies Who Want to Destroy You." The enemies: the National Audubon Society and the National Wildlife Federation.

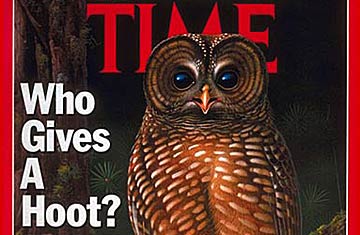

The mill owners, self-made men of considerable influence in their communities, are stunned that their livelihoods are threatened because of a nocturnal bird so unobtrusive that few have ever seen it. "We came out here in the 1850s," says Milton Herbert, the owner of Herbert Lumber in Riddle, Ore. "We spend our lives trying to understand trees, to live with the environment, not against it. I hunt and fish. This is my home. I get real uptight when I think they gave my ancestors 160 acres for homesteading, and they're giving the owl 2,200 acres." He is perplexed by calls to preserve the ancient forest. "They're trying to stop time, and that's one thing we can't do," says Herbert. "Bugs, fire or man are going to harvest the trees; they don't live forever." That's the industry's view. Timber is a crop, simple as that. Rod Greene, logging manager with Sun Studs Inc. in Roseburg speaks of the old growth as "overripe," "wasteful" and "inefficient." Behind him, as far as the eye can see, in 55-ft.-stacks, rises the mill's inventory of tree trunks, more than 13,000 trees that once covered 300 acres or more. Gobbling up some 320 trees a day, the mill will consume the inventory in less than six weeks. Inside, computers align the logs by laser, then blades unwrap them like rolls of paper towel, spinning out a ribbon of veneer 8 ft. wide and four miles long every hour. Other machines carve out 3,000 "studs," or construction posts, every hour, 20 hours a day, seven days a week. In town after town, the scene is repeated. Nature cannot keep pace.