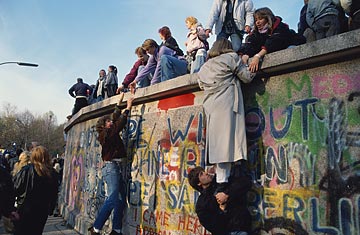

Crowds bear witness to the fall of the Berlin Wall on Nov. 10, 1989

(6 of 7)

Much will depend, of course, on whether, and how soon, Krenz delivers on his rhetoric of freedom. The conviction that they will be able to decide their future could indeed keep at home most East Germans who are now tempted to flee; it is difficult to see anything else that might. Until the opening of the Wall, however, Krenz's reformist inclinations had seemed ambiguous. For many years he had been a faithful follower of Honecker's, and as recently as September defended the Chinese government's bloody suppression of pro- democracy demonstrators in Beijing's Tiananmen Square. His conversion seemed sparked less by ideological conviction than by a desperate desire to cling to power in the face of street protest and refugee hemorrhage.

Even some of last week's moves were ambiguous. The mass resignation of the 44-member Cabinet was not so significant as it was dramatic, since the Cabinet had been a rubber stamp. Its dismissal, however, did serve to rid Krenz of Premier Willi Stoph, a Honecker loyalist. The dissolution of the 21-member Politburo, and its replacement with a slimmer ten-member body, was far more pointed, since that is where the real power lies. Some of its more notorious hard-liners got the ax, including Stoph; Erich Mielke, head of the despised state security apparatus; and Kurt Hager, chief party ideologist. Hans Modrow, 61, the Dresden party leader, was named to the Politburo and will be Premier in the new government. He has been likened alternately to Gorbachev and Boris Yeltsin, the reformist thorn in the Soviet President's side. Some conservatives, however, remain in the reshaped Politburo, and the way Krenz rammed his slate through the Central Committee was scarcely an exercise in democracy.

The initial reforms, in any case, did not satisfy the opposition. "Dialogue is not the main course, it is just the appetizer," proclaimed Jens Reich, a molecular biologist and leader of New Forum, the major dissident organization. Founded only in September, it claims 200,000 adherents and has just been recognized by the government, which originally declared it illegal. The opposition pledged to keep up the pressure for a free press, free elections and a new constitution stripped of the clause granting the Communist Party a monopoly on power.

The Central Committee responded in co-opting language. "The German Democratic Republic is in the midst of an awakening," it declared. "A revolutionary people's movement has brought into motion a process of great change." Besides underlining its commitment to free elections, the committee promised separation of the Communist Party from the state, a "socialist planned economy oriented to market conditions," legislative oversight of internal security, and freedom of press and assembly.

Thus, rhetorically at least, the opposition no longer gets an argument from the government. Gerhard Herder, East German Ambassador to the U.S., pledged reforms that "will radically change the structure and the way the G.D.R. will be governed. This development is irreversible. If there are still people alleging that all these changes are simply cosmetic, to grant the survival of the party, then let me say they are wrong."