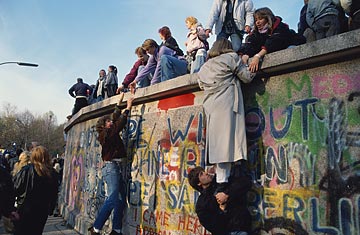

Crowds bear witness to the fall of the Berlin Wall on Nov. 10, 1989

(2 of 7)

The collapse of the old regimes and the astonishing changes under way in the Soviet Union open prospects for a Europe of cooperation in which the Iron Curtain disappears, people and goods move freely across frontiers, NATO and the Warsaw Pact evolve from military powerhouses into merely formal alliances, and the threat of war steadily fades. They also raise the question of German reunification, an issue for which politicians in the West or, for that matter, Moscow have yet to formulate strategies. Finally, should protest get out of hand, there is the risk of dissolution into chaos, sooner or later necessitating a crackdown and, possibly, a painful turn back to authoritarianism.

In East Germany the situation came close to spinning out of control. Considered a hard-liner, Krenz succeeded the dour Erich Honecker as party chief only three weeks ago, and eleven days after a state visit by Mikhail Gorbachev. Ever since, Krenz has had to scramble to find concessions that might quiet public turmoil and enable him to hang on to at least a remnant of power. He has been spurred by a series of mass protests -- one demonstration in Leipzig drew some 500,000 East Germans -- demanding democracy and freedoms small and large, and by a fresh wave of flight to the West by many of East Germany's most productive citizens. So far this year, some 225,000 East Germans out of a population of 16 million have voted with their feet, pouring into West Germany through Hungary and Czechoslovakia at rates that last week reached 300 an hour. Most are between the ages of 20 and 40, and their departure has left behind a worsening labor shortage. Last week East German soldiers had to be pressed into civilian duty to keep trams, trains and buses running.

The Wall, of course, was built in August 1961 for the very purpose of stanching an earlier exodus of historic dimensions, and for more than a generation it performed the task with brutal efficiency. Opening it up would have seemed the least likely way to stem the current outflow. But Krenz and his aides were apparently gambling that if East Germans lost the feeling of being walled in, and could get out once in a while to visit friends and relatives in the West or simply look around, they would feel less pressure to flee the first chance they got. Beyond that, opening the Wall provided the strongest possible indication that Krenz meant to introduce freedoms that would make East Germany worth staying in. In both Germanys and around the world, after all, the Wall had become the perfect symbol of oppression. Ronald Reagan in 1987, standing at the Brandenburg Gate with his back to the barrier, was the most recent in a long line of visiting Western leaders who challenged the Communists to level the Wall if they wanted to prove that they were serious about liberalizing their societies. "Mr. Gorbachev, open this gate!" cried the President. "Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!" There was no answer from Moscow at the time; only nine months ago, Honecker vowed that the Wall would remain for 100 years.