(3 of 9)

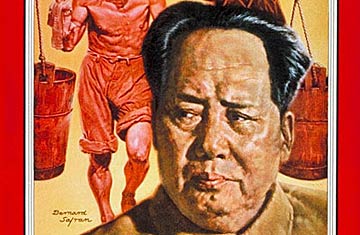

The Cave Dweller. Mao Tse-tung, who was born in the farming village of Shao Shan in the "rice bowl" province of Hunan, hated his father, a "rich," i.e., solvent, peasant who beat his sons often, gave them, as Mao bitterly remembers, "no money and the most meager food." After drifting through half a dozen schools. Mao at 24 got a job as assistant to Li Ta-chao, the Marxist librarian of Peking University, and finally found his hammer. In May 1921, he was one of twelve men who met in Shanghai to organize the Chinese Communist Party, though, according to one of his cronies, he "seemed to know little about Marxism."

In 1924 when the Chinese Communists, at Joseph Stalin's order, formed a coalition with the Kuomintang, Mao went along dutifully enough. But he was not convinced by Stalin's insistence that the Communist revolution must base itself on China's negligible urban proletariat. And when Chiang Kai-shek in a lightning stroke against his erstwhile allies all but wiped out the Chinese Communist Party in April 1927, Mao set out for his native Hunan to test his heretical belief that a successful Communist revolution in China must be based on the peasantry.

Mao's first, unauthorized attempt to organize a peasant uprising promptly got him expelled from the Chinese Communist Politburo. But within four years his "Chinese Soviet Republic," headquartered in a Buddhist temple on rugged Chingkan Mountain in Kiangsi province, was the most powerful Communist force in China. Five times Chiang Kai-shek's armies launched "campaigns of extermination" against the Communists; finally, in 1934, Mao's troops broke through the Nationalist lines and began their epic, 6,000-mile Long March to desolate Yenan in North China. When they reached their remote destination after fighting their way over 18 mountain ranges, less than a quarter of the 90,000 men who had begun the march were left. Of this remnant—and hence of the Chinese Communist Party—Mao was the unchallenged leader.

In the early Yenan years Mao, like most of his followers, lived in a cave. But from this rude lair, Mao succeeded in forcing Chiang Kai-shek to accept the Communists as allies in the "patriotic war" against Japan. Mao himself was primarily interested in profiting from chaos. "Our determined policy," he explained, "is 70% self-development, 20% compromise, and 10% fight the Japanese." Result was that in 1945 when Chiang Kai-shek emerged from his wartime back-country capital of Chungking, his power was largely confined to China's big cities; Communist forces, now over a million strong, roamed the countryside almost at will. The U.S. spectacularly failed in a politically naive postwar effort to bring Communists and Nationalists together, and by December 1949, what was left of Chiang's shattered armies was fleeing to Formosa.