(2 of 9)

Exaggerated though such fears may be, they are not frivolous. As recently as World War II Winston Churchill could impatiently dismiss as "unrealistic" U.S. insistence that China have big-power status. Yet today, barely 15 years later. Red China is universally acknowledged as the most formidable military power in Asia, can throw into action at any time more jet planes (over 2,000) and more troops (over 2,000,000) than all the rest of the East Asian powers combined. Within the Communist bloc, when China speaks, Khrushchev listens.

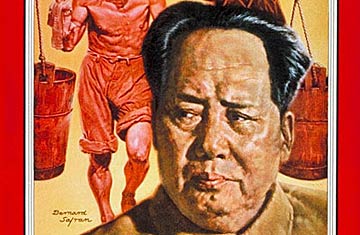

The Glowing Image. More than any other government in the world today. Red China is the long shadow of one man. At 65, Chairman-Mao Tse-tung is at once China's emperor, pope and father image. Like Stalin in his heyday, Mao is quoted as the ultimate authority on ideology, military science, steel production, poetry, art, and the uses of fertilizer. Every proclaimed achievement begins with the phrase "Thanks to Chairman Mao." His public appearances arouse excitement bordering on hysteria, evoke near tearful tributes to his "affectionate and kindly gaze.'' Nor are foreigners immune to his spell: Brazilian Sculptor Maria Martins recalls him as "a glowing image—a genius in terms of 20th century politics and a sage out of ancient China."

When he is not touring his domain dispensing advice to athletes, farmers and lady cops, Mao lives with his fourth wife, exActress Lan Ping, and two teen-age daughters in the Imperial City's "Perpetuating Harmony House." No lover of regular office hours, he works either at home or, in good weather, in a tent set up in the park outside. Once a heavy smoker (50 or more British 555s a day), he now, on doctor's orders, confines himself to a pack a day, keeps fit by swimming in a luxurious pool in the Imperial City. For relaxation he writes classical Chinese poetry—a pastime his regime is otherwise discouraging by switching Chinese from their traditional ideographs to a Romanized alphabet.

For all his scholarly air, Mao is almost totally ignorant of science (which he dislikes) and, by the testimony of one of his former teachers, is "terrible at mathematics." Except for whatever he may have picked up on two brief trips to Moscow, he knows the world outside China only at secondhand, and according to Chang Kuo-tao, once his colleague on the Chinese Communist Politburo, he is a poor administrator ("Vague about details and has a rather poor memory about people who are not constantly around him"). Essentially, Mao's world is an imaginary one—a curious melange of Chinese monarchical concepts and Marxist ideology. And behind the benevolent, Buddha-like gaze lie vast personal ambition and ruthless purpose. To a sentimental intellectual who once suggested that "Communism is Love," Mao replied: "No, comrade, Communism is not love; it is a hammer which we use to destroy the enemy."