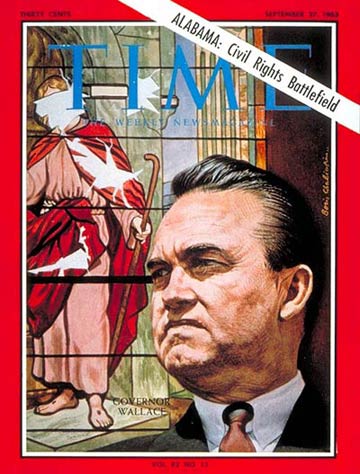

Alabama Gov. George Wallace

(6 of 7)

Said Bobby to his brother: "If he still doesn't move, we'll try and get by him." Asked the President: "Push him?" Replied Bobby: "We might push him a little bit."

The strategy worked. Wallace refused Katzenbach's first request. Bobby got word of that almost immediately. He picked up the phone and called the President. "You heard? . . . Will you sign the proclamation? . . . Sign it now."

Shortly after that, Katzenbach returned to the campus with the National Guard commander and the Special Forces men. There was no need to push. Wallace, retreating once more, stepped aside.

To much of the nation, it seemed that Wallace had acted out a charade, then abjectly surrendered. But not to most white Alabamians, who admired their Governor more than ever as a doughty little defender of segregation. In that atmosphere came the opening this month of Alabama's public elementary and high schools. Birmingham, Mobile, Tuskegee and Huntsville were scheduled to start their integration. Wallace got state troopers, in cars with tags emblazoned by the Confederate flag, to interfere with integration in all four cities. The Federal Administration rather easily outmaneuvered him: President Kennedy again ordered the Alabama National Guard into federal service, and Wallace was beaten. Again Wallace backed away from a real showdown. But again he had aroused violent passions—which led to the Sunday school bombing.

Ready to Shoot. In their angry and anguished protest to that bombing, Alabama Negro leaders such as Martin Luther King and the Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth at first demanded that President Kennedy send troops to take over Birmingham. But later last week King, Shuttlesworth and some other Negro leaders went to the White House, talked to the President, and were persuaded to rescind their demand. Instead, they accepted the President's offer to send Earl Blaik, onetime West Point football coach, and Kenneth Royall, former Secretary of the Army and a native North Carolinian, to Birmingham to attempt to mediate racial disputes in the strife-torn city.

In fact, the Blaik-Royall mission was little more than a gesture, a way of indicating Administration concern about Birmingham without bringing on a real federal showdown with Alabama. With a presidential election year coming up, the Democratic Administration is understandably anxious to avoid any such showdown with the once-solid Democratic South. For in a purely political sense, the bitter differences between the Northern and Southern branches of the Democratic Party carry as explosive a potential as any ever dreamed of by a Birmingham bomber.

Alabama's George Wallace is happily aware of that fact, and indeed he is planning to run for President himself next year. It is not that he hopes to win, but that he hopes to hurt Kennedy. Last week in his Montgomery office, he riffled through the mail that has piled high on his desk.