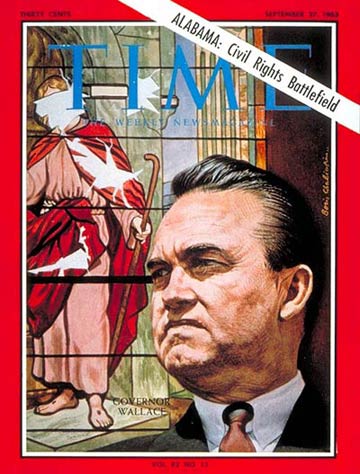

Alabama Gov. George Wallace

(5 of 7)

Yet in running for Governor in 1958, Wallace did not campaign as a diehard defender of segregation, but as a candidate who would work to bolster Ala bama's economy, build better schools and better highways. He was defeated in the Democratic primary by John Patterson (TIME cover, June 2, 1961), who did run on an all-out segregationist plat form. In that defeat Wallace learned a lesson. "They just out-segged me," he said to friends. "They're never going to do that again."

They never have. Wallace ran again for Governor in 1962, and this time he was spouting segregationist fire that burned hotter than Vulcan's torch. "As your Governor," he cried, "I shall refuse to abide by illegal court orders to the point of standing at the school-house door if necessary."

Ready for Reaping. Largely on the basis of his pledge to stand in the schoolhouse door, Wallace was easily elected Governor—and he soon got a chance to live up to his promise. Under federal court order, two Negroes, James Hood and Vivian Malone, were scheduled to enroll in the University of Alabama at Tuscaloosa last June. For months prior to that, University President Frank Rose had painstakingly planned to comply with the court order in a way that would avoid violence. Rose made it perfectly plain that he did not want Wallace butting in.

But Wallace was undaunted. He would, he still insisted, bar the way to the Negro students; apparently he wanted to force federal marshals to arrest him and haul him off to jail. To be sure, his action might result in some bloodletting, but there seemed plenty of political profits ready for reaping.

In Washington, Attorney General Bobby Kennedy and the White House were determined that Wallace would not get his way. For days the Attorney General and his staff studied a variety of contingency plans. They examined maps, plotted troop movements. Deputy Attorney General Nick Katzenbach set up headquarters in Tuscaloosa. Federal marshals were assembled. Justice Department Aide John Doar briefed the two prospective Negro students ("You should dress as though you were going to church, modestly, neatly").

A Little Push. Shortly before the big day, Bobby and several aides drove to the White House and sat down with the President to lay out their plans. Katzenbach, explained Bobby, would drive to the campus with the two Negroes and leave them in the car. He would walk up to the school entrance where Wallace would be waiting. Katzenbach would ask Wallace politely to step aside and permit the students to enter, as the federal court had ordered. Wallace presumably would refuse. Katzenbach would then order the students to be taken to their dormitories. Bobby would be notified and in turn would tell the President, who would then sign a prepared executive order federalizing the National Guard. Katzenbach would return to the school door and again confront Wallace. This time he would have with him the National Guard commander and four beret-capped Special Forces soldiers. The commander would ask the Governor to let the students pass. If Wallace again refused, the G.I.'s would form a tight wedge and try to move on through.