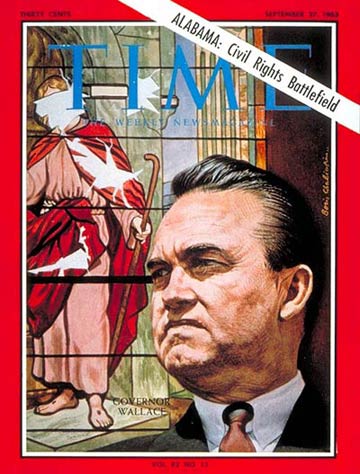

Alabama Gov. George Wallace

(3 of 7)

Without Bicker or Bother. Below the northern tier is the Black Belt, cutting a 100-mile-deep, 14-county swath across the state. The Black Belt got its name not so much for its concentration of Negroes as for its fertile dark brown soil. Once the heart of Alabama's cotton kingdom, the rolling, sparsely populated belt has changed radically in recent years: the houses where cotton sharecroppers once lived are now stuffed with hay to feed cattle, for livestock raising has become Alabama's No. 1 agricultural business.

Racist sentiment runs high in the Black Belt. This feeling certainly includes the belt's major city—and state capital—of Montgomery (pop. 134,000), which prides itself on its wide avenues, colonnaded houses, and its devotion to the cause of segregation. It was in Montgomery that Martin Luther King Jr. seven years ago won a boycott-battle to integrate the city's buses; yet today Montgomery whites contentedly point out that most Negroes still sit in the rear of buses because "that's where they like to ride."

To the south is the narrow corridor that gives Alabama access to the sea. The major seaport city of Mobile (pop. 202,000) likes to think of itself as a miniature New Orleans. A cosmopolitan place, Mobile exudes a certain Southern charm, with towering live oaks along the streets, and botanical gardens featuring beautiful azaleas and camellias. Though the harbor is Mobile's chief resource, industry too has come to town: Alcoa is there, along with a couple of paper mills and a fast-growing chemical industry. Like Huntsville, Mobile quietly desegregated its lunch counters without bicker or bother.

"Bombingham." And then there is Birmingham—an entity of its own, a region of the mind. A sooty, sprawling city of 340,000, Birmingham has been called the Pittsburgh of the South. Yet except for its location, it is hardly a Southern city at all.

The center of an area rich in minerals, ranging from iron ore to arsenic, Birmingham was only founded in 1871, has none of the antebellum traditions or grace of the Old South. Its symbol since 1936 has been a forbidding 60-ton, 50-ft.-high, aluminum-coated statue of Vulcan, who was the Roman god of fire. Vulcan, high atop Red Mountain, drew workers like moths from all over the state. Most of them were unschooled, out-of-work farm people, attracted by the promise of prosperous city life.

But instead of finding that life, they found only more poverty, sporadic unemployment—and the threat of job competition from the city's large (40%) Negro population. The result is described by University of Alabama Philosophy Professor Iredell Jenkins in a perceptive if unprofessorial comment. "The obvious thing about Birmingham," says Jenkins, "is that there's just a lot of goddam white trash that's conglomerated there." It is, therefore, no coincidence that since 1947 "Bombingham" has known 50 bombings that can be ascribed to racial conflict—and not one of them has been solved.

All this, then, is Governor George Wallace's Alabama—and he is a true product of his state, with all its conflicts and contrasts, its red moons, pine forests and roiling yellow rivers.