(4 of 11)

In all, more than 400 white churchmen sped to Selma. Many turned up without so much as a toothbrush or a change of socks, and few had any idea of where they would stay. Some seemed to think it was all something of a lark. Said one clergyman to a colleague as he stepped off the plane in Montgomery: "Fix bayonets! Charge!" Also on hand were secular crusaders, including Mrs. Paul Douglas, wife of Illinois' Democratic Senator, Mrs. Harold Ickes, widow of Franklin Roosevelt's Interior Secretary, and Mrs. Charles Tobey, widow of the former Republican Senator from New Hampshire.

Head It Off. Colonel Al Lingo was in Selma too—this time with 500 state troopers, leaving only about 250 to attend to the rest of Alabama's law-enforcement requirements. FBI agents drifted unobtrusively into town. Straw-bossing federal activities was John Doar, Assistant U.S. Attorney General in charge of civil rights. As a personal mediator sent by President Johnson came LeRoy Collins, onetime Democratic Governor of Florida, now chairman of the Community Relations Service, which was established under the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Collins' orders from Johnson were to head off trouble at all costs. He succeeded, for the time being. But in the arrangements to secure peace, it turned out that a lot of the principals' egos were bigger than their principles.

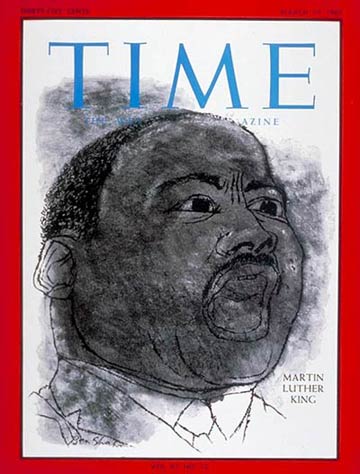

What became essentially a charade started at 4:30 on Monday afternoon. Four attorneys for Martin Luther King appeared in the Montgomery office of U.S. District Judge Frank M. Johnson Jr. They wanted him to issue an injunction to keep state and Dallas County police from interfering with the Tuesday march.

Johnson, 46, is a tough-minded jurist and a native Alabamian who attended a state university with George Wallace. The two were once friendly, but have long since fallen out—mostly over civil rights. Wallace, in fact, once referred obliquely to Judge Johnson without actually naming him as an "integrating, scalawagging, carpetbagging liar."

Johnson told the lawyers that he would have to hear evidence on their petition, and scheduled a hearing for Thursday, the first available date. Until the matter was settled, Johnson advised, King should call off the Tuesday march. At 9 o'clock that night, the attorneys called the judge to say that King agreed.

That very night, in the home of a Negro dentist in Selma, King was undergoing intense pressures and conflicts. His instinct was to go along with Judge Johnson and postpone the march. He was fearful of provoking another savage onslaught by state troopers and Sheriff Clark's men. But he was also smarting under criticism for having absented himself from the Sunday march. And he felt an obligation to the out-of-state clergymen and others who had come to march.