Despite great gains in the past decade, the American Negro is still often denied the most basic right of citizenship under constitutional government —the right to vote.

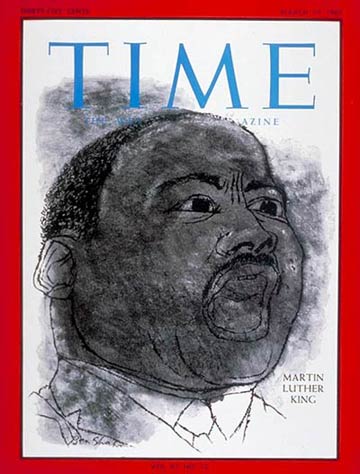

Last week the Negro's struggle to achieve that right exploded into an orgy of police brutality, of clubs and whips and tear gas, of murder, of protests and parades and sit-ins in scores of U.S. cities and in the White House itself. It was a week in which the potential for further violence was so great that President Johnson signed an order that would have dispatched federal troops to Alabama on a moment's notice. It was a week of intense pressures and back-room dealings, of quick emotionalism and easily achieved righteousness. And it was a very trying week for the foremost leader of the civil rights movement, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

Amid the controversy and chaos, it was easy to lose sight of the central point: voting rights. But that was what Selma, Alabama, was all about.

The Bullyboy. Selma is a city of 29,500 people—14,400 whites, 15,100 Negroes. Its voting rolls are 99% white, 1% Negro. More than a city, Selma is a state of mind. "Selma," says a guidebook on Alabama, "is like an old-fashioned gentlewoman, proud and patrician, but never unfriendly." In Selma, Negroes are supposed to know their place. A Selma ordinance of 1852 declared that "any Negro found upon the streets of the city smoking a cigar or pipe or carrying a walking cane must be on conviction punished with 39 lashes"—and the place has not changed much since. Generations-old Greek Revival homes grace the white residential district; the Hotel Albert, built with slave labor and patterned after the Doge's Palace in Venice, is a first-rate inn. But the symbol of Selma is Sheriff James Clark, 43, a bully-boy segregationist who leads a club-swinging, mounted posse of deputy volunteers, many of them Ku Klux Klansmen.

It was in Selma, four years ago, that the Federal Government filed its first voting-rights suit. Other civil rights suits have been filed since, four of them directed at Sheriff Clark personally; but court processes are slow, and Selma Negroes remain unregistered.

Since the desire to dramatize the Negro plight goes hand in hand with the more substantive drive to achieve equal rights, Selma seemed a natural target to Martin Luther King. The city's civil rights record was awful. There was Clark, the perfect public villain. There, too, was Mayor Joe T. Smitherman, 35, an erstwhile appliance dealer, an all-out segregationist, and a close friend of Alabama's racist Democratic Governor George Wallace.

Thus, two months ago, King zeroed in on Selma. A magnetic leader and a spellbinding orator, he rounded up hundreds of Negroes at a time, led them on marches to the county courthouse to register to vote. Always, Clark awaited them, either turning them away or arresting them for contempt of court, truancy, juvenile delinquency and parading without a permit. Those who actually reached the registrars were required to file complicated applications and take incredibly difficult "literacy" tests that few if any could pass. Several times the drive faltered—but each time Clark revived it by committing some new outrage.

The First Martyr. In seven weeks, Clark jailed no fewer than 2,000