About 50 crisis counselors work in New York Citys 24/7 suicide-prevention center. Calls to the national lifeline increase 15% a year.

The bridge phone inside New York City's suicide-prevention call center rings only about once a month. But when it does, often in the middle of the night, it emits distinct, deep chirps--as if the phone itself is in distress. The operators manning the 24/7 LifeNet hotline recognize the sound immediately. It means someone's calling from one of the 11 area bridges, and they're likely thinking about jumping.

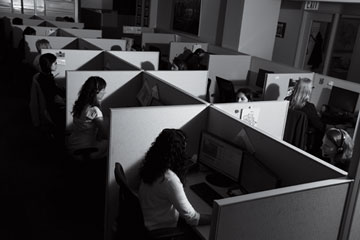

LifeNet, a mental-health and suicide-prevention hotline servicing the New York City metropolitan area, is one of 161 call centers that make up the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline network, which is headquartered in the same building. During its busiest hours, from 9 a.m. to 7 p.m., the hotline has roughly 20 operators working the phones inside an unassuming L-shaped office space in lower Manhattan. The operators could be mistaken for telemarketers. A large computer screen at the head of the call center showing the number of lines being processed might just as easily be registering orders for exercise equipment or beauty products.

You don't get a sense of what actually happens in this room until you run across the bridge phone, which is a direct line to the call center--LifeNet's equivalent of the Oval Office's mythical red phone. On the wall above it, black picture frames from Ikea display detailed information for each bridge and the locations of its call boxes: "Northbound 3rd Avenue Exit," "Westbound Light Pole 60." If someone calls, counselors can match the caller ID with the information above the phone and immediately send help.

Suicide rates have been climbing in the U.S. since 2005. In 2009 the number of suicides surpassed deaths from motor-vehicle accidents for the first time. In 2010, the most recent year for which statistics are available, 38,364 Americans killed themselves, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. From 1999 to 2010, the suicide rate for Americans ages 35 to 64 rose 28.4%. For men in their 50s, the rate rose nearly 50% during that time. And because many suicides go unreported, most researchers believe these numbers undercount the true totals.

The rising number of Americans committing suicide has led to a debate over how best to prevent it. Over the past 15 years, public policy and federal funding have shifted toward a broader mental-wellness movement aimed at helping people deal with anxiety and depression that could eventually lead to suicidal ideation. But critics of the shift worry that it may have left those most at risk of suicide without the support they need.

Experts in the field often use the metaphor of a river to illustrate the divide: Should prevention efforts try to reach a larger group of people upstream, offering counsel before they become suicidal, or concentrate resources on a smaller but closer-to-the-edge group downstream? If it were up to those who work at LifeNet, the bridge phone would not exist at all. "We don't necessarily want to get people who are on the edge of the waterfall," says John Draper, director of the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. "If they are, we can help them. But it's a huge cost savings for the entire mental-health system if you can get people further upstream."