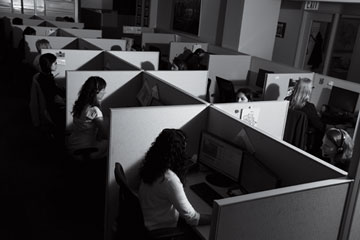

About 50 crisis counselors work in New York Citys 24/7 suicide-prevention center. Calls to the national lifeline increase 15% a year.

(4 of 6)

According to the National Institute of Mental Health, 90% of people who die by suicide in the U.S. suffer debilitating mental illness or a substance-abuse disorder often in conjunction with other mental disorders. Other risk factors include prior suicide attempts, a family history of mental illness and violence in the home. If we know who's most at risk, people like Jaffe and Berman argue, shouldn't we target them in a smarter way? If a factory closes, for example, shouldn't efforts be made to market prevention services in that community?

SAMHSA is the federal government's suicide-prevention arm. Though mental-health coverage has been expanded for tens of millions of Americans as part of the Affordable Care Act, SAMHSA's funding requests for suicide-prevention efforts have decreased over the past two years. For fiscal 2014, SAMHSA requested $50 million for its suicide-prevention measures, $8 million less than in 2012. The agency gives $3.7 million annually to the Lifeline. Funding for National Suicide Prevention Lifeline crisis centers to provide follow-up to suicidal callers and evaluate the lifeline's effectiveness, which once ranged from $700,000 to $1.7 million a year, was cut completely. SAMHSA did, however, request a $2 million increase for the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention, which, among other things, would be used to develop and test nationwide awareness campaigns.

Richard McKeon, the acting chief of SAMHSA's suicide-prevention branch, says its strategy has always focused on those most at risk: "Much of our suicide portfolio focuses on those who are actively suicidal." He says that focus is evident in the national strategy, which was revised last year to offer a comprehensive approach to preventing suicide at the local level. But he acknowledges that the behavioral health of the entire population is also a priority. "Our suicide-prevention efforts do take place within a broad public-health context," he says. "Ideally, we'd like to be able to prevent people from becoming suicidal in the first place."

The Good Behavior Game, a program designed to identify early behavioral-health problems, to which SAMHSA awarded $11 million over five years, is one initiative McKeon points to that catches people upstream. It's used in 22 economically disadvantaged school systems across the country and has been cited as effective by the Institute of Medicine. "A lot of the work we do is aimed at identifying youth who are at most serious risk right now," he says. "We are dealing with a lot of high-risk situations among very vulnerable people, but there's also solid scientific basis for early interventions."

The scientific case for public-awareness campaigns is far less solid. A 2009 study in the journal Psychiatric Services looked at 200 publications from 1987 to 2007 describing depression- and suicide-awareness programs targeted at the public and found that they "contributed to modest improvement in public knowledge of and attitudes toward depression or suicide," but it could not find that the campaigns actually helped increase care-seeking or decrease suicidal behavior. A similar study in 2010, in the journal Crisis, found that billboard ads actually had negative effects on adolescents, making them "less likely to endorse help-seeking strategies."