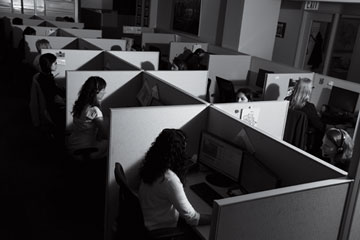

About 50 crisis counselors work in New York Citys 24/7 suicide-prevention center. Calls to the national lifeline increase 15% a year.

(3 of 6)

In the 1980s, Draper was part of a team of mobile crisis clinicians who went into the homes of people who were psychiatrically ill but unable or unwilling to get help. The experience convinced him that a major problem with the country's mental-health system was that it waited for those in need to seek it out, which many who would most benefit from it aren't able to do. "It says, 'O.K., you're mentally ill? I'll see you Tuesday at 9 a.m. Hope you can make it.' The system is not set up for the convenience of the user," Draper says. "As a result, two-thirds of people with mental-health problems never seek care."

Draper's conviction that the system was in need of reform brought him to the Mental Health Association of New York City, where he helped launch a 24/7 crisis information and referral network. LifeNet gained wide attention in 2001 when it became a central resource for those affected by the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks. People were reporting depression, anxiety and other traumatic responses in massive numbers. LifeNet's call volume and staff doubled, and they haven't gone down since. In 2004 the hotline was chosen by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) to administer the national suicide-prevention lifeline.

Today, Draper and his staff oversee more than 160 networked call centers around the country. Call 1-800-273-TALK and you'll be routed to the call center closest to the number from which you're calling. About 8 million adults in the U.S. are thinking seriously about suicide, but only 1.1 million actually attempt it. So when Draper sees the volume actually reaching that 1.1 million number, which he expects it to this year, he views it as a good thing.

"If your calls are increasing, does that mean more people are in distress?" he asks. "That's not necessarily true. It means more people may have been in distress all along but didn't know this resource was there."

The challenge is determining whether suicide-prevention efforts are working. The only way you know if you're saving someone's life is if they come out and say so.

"The lifeline is a valuable addition to our efforts," says Dr. Lanny Berman, executive director of the American Association of Suicidology. "It's indeed a resource for people in suicidal crisis to reach out immediately and get help. Whether it is effective in saving lives remains to be seen."

CASTING A WIDE NET

Many suicide-prevention programs that receive federal funding are advertised nationwide, which critics like DJ Jaffe see as a misguided use of resources.

"A lot of suicide-prevention campaigns are based on reaching out for help if you're feeling depressed rather than calling if you're truly suicidal," says Jaffe, who founded the nonprofit advocacy group Mental Illness Policy Org after his sister-in-law was diagnosed with schizophrenia in the mid-1980s. "Spending massive amounts of money marketing to the public is a giant waste of money because we know where we can focus it."