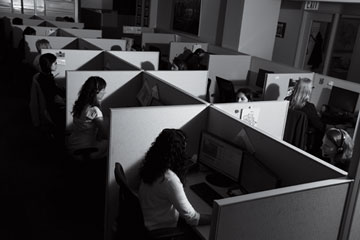

About 50 crisis counselors work in New York Citys 24/7 suicide-prevention center. Calls to the national lifeline increase 15% a year.

(2 of 6)

LIFENET, 10:15 A.M.

Dely Santiago puts on her black Sennheiser headset and takes a look at the queue. Five callers are waiting to speak with an operator. A dozen others are on the line.

Santiago is one of 50 employees who keep New York City's suicide-prevention call center running day and night. A psychotherapist and behavior-modification specialist, Santiago, 29, has been working at LifeNet since 2009. She uses just one phone, but 14 separate hotlines feed into it. They range from numbers given out for national and local mental-health issues to ones dedicated to victims of bullying, people struggling since Hurricane Sandy and language-specific hotlines. There is even an NFL Lifeline for those with football-related mental-health issues. Many operators are trained to answer all of them.

This morning, Santiago's first call is from OASAS Hopeline, the New York State hotline for substance abuse. While she can't tell who is calling, she always knows which line is coming through. If a LifeNet call pops up on her caller ID, it's often someone reaching out for basic information. That's low-stress. But if it's the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, she takes deep breaths before answering to stay calm. This one, the state addiction line, is somewhere in the middle.

Santiago runs through a series of questions to gauge the call's seriousness. Her voice is soothing, lilting even, but firm.

"You obtained a DWI in which county?"

"Has alcohol been an ongoing issue for you?"

"Any thoughts of suicide or hurting anybody else?"

The operators routinely ask callers whether they have suicidal thoughts, no matter which hotline they have called, because there's no way to tell whether a substance-abuse call will quickly turn into a suicide call. You just have to ask.

The queue doesn't let up. Several people are on hold. More are talking to operators. Once crisis counselors have finished a call, they get three minutes to log it into the database and take a breath before the phone rings again.

"Hello, LifeNet," Santiago says. "How may I help you?"

AT THE WATERFALL

The national suicide prevention Lifeline, of which LifeNet is part, deals with those who are upstream and downstream. The organization is marketed to the general public through billboards, transit displays and other outdoor advertising. The hotline is targeted at people suffering from anxiety, depression and loneliness but who may not be actively suicidal, while also serving as an emergency resource for those who are at immediate risk of killing themselves. Calls to the Lifeline increase by about 15% every year. This year, the organization expects to receive 1.1 million to 1.2 million.

Draper is the Lifeline's soft-spoken, goateed, ponytailed director and a wholehearted advocate for early treatment. A psychotherapist by training, he sounds like someone who has spent a lot of time counseling people in crisis. Draper speaks calmly but with purpose. He looks you in the eye. He routinely uses your name in conversation.