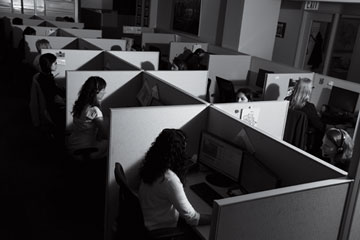

About 50 crisis counselors work in New York Citys 24/7 suicide-prevention center. Calls to the national lifeline increase 15% a year.

(5 of 6)

It's similarly hard to gauge how successful help lines are at deterring suicide. Several studies done in 2007 and 2012 by Columbia University's Madelyn Gould in cooperation with SAMHSA found that most callers who had contacted crisis centers felt less distressed emotionally and were less suicidal after the call. About 12% of suicidal callers reported in a follow-up interview that talking to someone at the lifeline prevented them from harming or killing themselves. Almost half followed through on a counselor's referral to seek emergency or mental-health services, and about 80% of suicidal callers said in follow-up interviews that the Lifeline had something to do with keeping them alive.

"I don't know if we'll ever have solid evidence for what saves lives other than people saying they saved my life," says Draper. "It may be that the suicide rate could be higher if crisis lines weren't in effect. I don't know. All I can say is that what we're hearing from callers is that this is having a real lifesaving impact."

LIFENET, 11:14 A.M.

It took a little less than an hour for Santiago to get her first call on the national suicide hotline.

The male caller has contacted the center six times since 7 a.m. In Spanish, he tells Santiago he's depressed, anxious. He's hearing things that aren't there and can't connect with his psychiatrist. He says he feels like he's going to die. None of this is unusual. This is the kind of thing that Santiago and the rest of the operators deal with every day, and they've increasingly been hearing from middle-aged men. Suicide rates for men ages 50 to 59 increased by almost 50% from 1999 to 2010. LifeNet's crisis counselors began observing a change in their callers when Wall Street crashed. More middle-aged men started calling with serious financial concerns.

While rates went up in cities across the country, rural areas saw even bigger jumps. Wyoming has the highest suicide rates of any state. Park County, home to Yellowstone National Park, had 45 suicides per 100,000 people in 2012. The national average is closer to 12 suicides per 100,000 people.

"In Wyoming, we have a tough-it-out mentality," says Terresa Humphries-Wadsworth, who coordinates the state's suicide-prevention efforts. "Locally, they call it 'Cowboy up'--being very independent, solving problems for yourself."

Rural areas have historically had higher suicide rates than urban areas, and most experts believe it's a combination of more gun ownership per capita, isolation and a culture that discourages seeking help. In the suicide-prevention field, Wyoming is a perfect storm. Besides its "Cowboy up" mentality, the state has one of the highest gun-ownership rates in the U.S., the lowest population density outside Alaska and only one call center networked to the national lifeline.

To counteract the state's culture of self-sufficiency, the Wyoming Department of Health began reaching out to men who had attempted suicide and were willing to talk about it.