(4 of 11)

A Slip, a Fall And a $9,400 Bill The billing advocates aren't always successful. just ask Emilia Gilbert, a school-bus driver who got into a fight with a hospital associated with Connecticut's most venerable nonprofit institution, which racked up quick profits on multiple CT scans, then refused to compromise at all on its chargemaster prices. Gilbert, now 66, is still making weekly payments on the bill she got in June 2008 after she slipped and fell on her face one summer evening in the small yard behind her house in Fairfield, Conn. Her nose bleeding heavily, she was taken to the emergency room at Bridgeport Hospital.

Along with Greenwich Hospital and the Hospital of St. Raphael in New Haven, Bridgeport Hospital is now owned by the Yale New Haven Health System, which boasts a variety of gleaming new facilities. Although Yale University and Yale New Haven are separate entities, Yale–New Haven Hospital is the teaching hospital for the Yale Medical School, and university representatives, including Yale president Richard Levin, sit on the Yale New Haven Health System board.

"I was there for maybe six hours, until midnight," Gilbert recalls, "and most of it was spent waiting. I saw the resident for maybe 15 minutes, but I got a lot of tests."

In fact, Gilbert got three CT scans — of her head, her chest and her face. The last one showed a hairline fracture of her nose. The CT bills alone were $6,538. (Medicare would have paid about $825 for all three.) A doctor charged $261 to read the scans.

Gilbert got the same troponin blood test that Janice S. got — the one Medicare pays $13.94 for and for which Janice S. was billed $199.50 at Stamford. Gilbert got just one. Bridgeport Hospital charged 20% more than its downstate neighbor: $239.

Also on the bill were items that neither Medicare nor any insurance company would pay anything at all for: basic instruments and bandages and even the tubing for an IV setup. Under Medicare regulations and the terms of most insurance contracts, these are supposed to be part of the hospital's facility charge, which in this case was $908 for the emergency room.

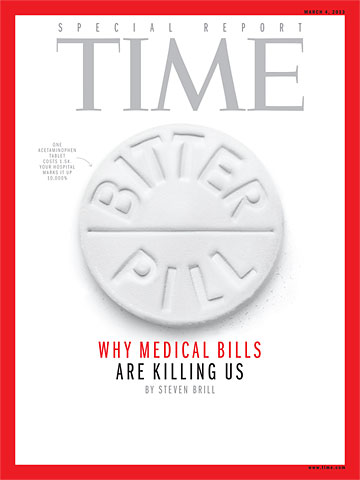

Javier Sirvent for TIME

Emilia Gilbert Slipped and fell in June 2008 and was taken to the emergency room. She is still paying off the $9,418 bill from that hospital visit in weekly installments. Her three CT scans cost $6,538. Medicare would have paid about $825 for all three

Gilbert's total bill was $9,418.

"We think the chargemaster is totally fair," says William Gedge, senior vice president of payer relations at Yale New Haven Health System. "It's fair because everyone gets the same bill. Even Medicare gets exactly the same charges that this patient got. Of course, we will have different arrangements for how Medicare or an insurance company will not pay some of the charges or discount the charges, but everyone starts from the same place." Asked how the chargemaster charge for an item like the troponin test was calculated, Gedge said he "didn't know exactly" but would try to find out. He subsequently reported back that "it's an historical charge, which takes into account all of our costs for running the hospital."

Bridgeport Hospital had $420 million in revenue and an operating profit of $52 million in 2010, the most recent year covered by its federal financial reports. CEO Robert Trefry, who has since left his post, was listed as having been paid $1.8 million. The CEO of the parent Yale New Haven Health System, Marna Borgstrom, was paid $2.5 million, which is 58% more than the $1.6 million paid to Levin, Yale University's president.

"You really can't compare the two jobs," says Yale–New Haven Hospital senior vice president Vincent Petrini. "Comparing hospitals to universities is like apples and oranges. Running a hospital organization is much more complicated." Actually, the four-hospital chain and the university have about the same operating budget. And it would seem that Levin deals with what most would consider complicated challenges in overseeing 3,900 faculty members, corralling (and complying with the terms of) hundreds of millions of dollars in government research grants and presiding over a $19 billion endowment, not to mention admitting and educating 14,000 students spread across Yale College and a variety of graduate schools, professional schools and foreign-study outposts. And surely Levin's responsibilities are as complicated as those of the CEO of Yale New Haven Health's smallest unit — the 184-bed Greenwich Hospital, whose CEO was paid $112,000 more than Levin.

"When I got the bill, I almost had to go back to the hospital," Gilbert recalls. "I was hyperventilating." Contributing to her shock was the fact that although her employer supplied insurance from Cigna, one of the country's leading health insurers, Gilbert's policy was from a Cigna subsidiary called Starbridge that insures mostly low-wage earners. That made Gilbert one of millions of Americans like Sean Recchi who are routinely categorized as having health insurance but really don't have anything approaching meaningful coverage.

Starbridge covered Gilbert for just $2,500 per hospital visit, leaving her on the hook for about $7,000 of a $9,400 bill. Under Connecticut's rules (states set their own guidelines for Medicaid, the federal-state program for the poor), Gilbert's $1,800 a month in earnings was too high for her to qualify for Medicaid assistance. She was also turned down, she says, when she requested financial assistance from the hospital. Yale New Haven's Gedge insists that she never applied to the hospital for aid, and Gilbert could not supply me with copies of any applications.

In September 2009, after a series of fruitless letters and phone calls from its bill collectors to Gilbert, the hospital sued her. Gilbert found a medical-billing advocate, Beth Morgan, who analyzed the charges on the bill and compared them with the discounted rates insurance companies would pay. During two court-required mediation sessions, Bridgeport Hospital's attorney wouldn't budge; his client wanted the bill paid in full, Gilbert and Morgan recall. At the third and final mediation, Gilbert was offered a 20% discount off the chargemaster fees if she would pay immediately, but she says she responded that according to what Morgan told her about the bill, it was still too much to pay. "We probably could have offered more," Gedge acknowledges. "But in these situations, our bill-collection attorneys only know the amount we are saying is owed, not whether it is a chargemaster amount or an amount that is already discounted."

On July 11, 2011, with the school-bus driver representing herself in Bridgeport superior court, a judge ruled that Gilbert had to pay all but about $500 of the original charges. (He deducted the superfluous bills for the basic equipment.) The judge put her on a payment schedule of $20 a week for six years. For her, the chargemaster prices were all too real.

The One-Day, $87,000 Outpatient Bill Getting a patient in and out of a hospital the same day seems like a logical way to cut costs. Outpatients don't take up hospital rooms or require the expensive 24/7 observation and care that come with them. That's why in the 1990s Medicare pushed payment formulas on hospitals that paid them for whatever ailment they were treating (with more added for documented complications), not according to the number of days the patient spent in a bed. Insurance companies also pushed incentives on hospitals to move patients out faster or not admit them for overnight stays in the first place. Meanwhile, the introduction of procedures like noninvasive laparoscopic surgery helped speed the shift from inpatient to outpatient.

By 2010, average days spent in the hospital per patient had declined significantly, while outpatient services had increased even more dramatically. However, the result was not the savings that reformers had envisioned. It was just the opposite.

Experts estimate that outpatient services are now packed with so much hidden profit that about two-thirds of the $750 billion annual U.S. overspending identified by the McKinsey research on health care comes in payments for outpatient services. That includes work done by physicians, laboratories and clinics (including diagnostic clinics for CT scans or blood tests) and same-day surgeries and other hospital treatments like cancer chemotherapy. According to a McKinsey survey, outpatient emergency-room care averages an operating profit margin of 15% and nonemergency outpatient care averages 35%. On the other hand, inpatient care has a margin of just 2%. Put simply, inpatient care at nonprofit hospitals is, in fact, almost nonprofit. Outpatient care is wildly profitable.

"An operating room has fixed costs," explains one hospital economist. "You get 10% or 20% more patients in there every day who you don't have to board overnight, and that goes straight to the bottom line."

The 2011 outpatient visit of someone I'll call Steve H. to Mercy Hospital in Oklahoma City illustrates those economics. Steve H. had the kind of relatively routine care that patients might expect would be no big deal: he spent the day at Mercy getting his aching back fixed.

A blue collar worker who was in his 30s at the time and worked at a local retail store, Steve H. had consulted a specialist at Mercy in the summer of 2011 and was told that a stimulator would have to be surgically implanted in his back. The good news was that with all the advances of modern technology, the whole process could be done in a day. (The latest federal filing shows that 63% of surgeries at Mercy were performed on outpatients.)

Steve H.'s doctor intended to use a RestoreUltra neurostimulator manufactured by Medtronic, a Minneapolis-based company with $16 billion in annual sales that bills itself as the world's largest stand-alone medical-technology company. "RestoreUltra delivers spinal-cord stimulation through one or more leads selected from a broad portfolio for greater customization of therapy," Medtronic's website promises. I was not able to interview Steve H., but according to Pat Palmer, a medical-billing specialist based in Salem, Va., who consults for the union that provides Steve H.'s health insurance, Steve H. didn't ask how much the stimulator would cost because he had $45,181 remaining on the $60,000 annual payout limit his union-sponsored health-insurance plan imposed. "He figured, How much could a day at Mercy cost?" Palmer says. "Five thousand? Maybe 10?"

Steve H. was about to run up against a seemingly irrelevant footnote in millions of Americans' insurance policies: the limit, sometimes annual or sometimes over a lifetime, on what the insurer has to pay out for a patient's claims. Under Obamacare, those limits will not be allowed in most health-insurance policies after 2013. That might help people like Steve H. but is also one of the reasons premiums are going to skyrocket under Obamacare.

Chest X-Ray Patient was charged $333. the national rate paid by Medicare is $23.83

Steve H.'s bill for his day at Mercy contained all the usual and customary overcharges. One item was "MARKER SKIN REG TIP RULER" for $3. That's the marking pen, presumably reusable, that marked the place on Steve H.'s back where the incision was to go. Six lines down, there was "STRAP OR TABLE 8X27 IN" for $31. That's the strap used to hold Steve H. onto the operating table. Just below that was "BLNKT WARM UPPER BDY 42268" for $32. That's a blanket used to keep surgery patients warm. It is, of course, reusable, and it's available new on eBay for $13. Four lines down there's "GOWN SURG ULTRA XLG 95121" for $39, which is the gown the surgeon wore. Thirty of them can be bought online for $180. Neither Medicare nor any large insurance company would pay a hospital separately for those straps or the surgeon's gown; that's all supposed to come with the facility fee paid to the hospital, which in this case was $6,289.

In all, Steve H.'s bill for these basic medical and surgical supplies was $7,882. On top of that was $1,837 under a category called "Pharmacy General Classification" for items like bacitracin ($108). But that was the least of Steve H.'s problems.

The big-ticket item for Steve H.'s day at Mercy was the Medtronic stimulator, and that's where most of Mercy's profit was collected during his brief visit. The bill for that was $49,237.

According to the chief financial officer of another hospital, the wholesale list price of the Medtronic stimulator is "about $19,000." Because Mercy is part of a major hospital chain, it might pay 5% to 15% less than that. Even assuming Mercy paid $19,000, it would make more than $30,000 selling it to Steve H., a profit margin of more than 150%. To the extent that I found any consistency among hospital chargemaster practices, this is one of them: hospitals routinely seem to charge 2½ times what these expensive implantable devices cost them, which produces that 150% profit margin.

As Steve H. found out when he got his bill, he had exceeded the $45,000 that was left on his insurance policy's annual payout limit just with the neurostimulator. And his total bill was $86,951. After his insurance paid that first $45,000, he still owed more than $40,000, not counting doctors' bills. (I did not see Steve H.'s doctors' bills.)