(11 of 11)

"If you could figure out a way to pay doctors better and separately fund research ... adequately, I could see where a single-payer approach would be the most logical solution," says Gunn, Sloan-Kettering's chief operating officer. "It would certainly be a lot more efficient than hospitals like ours having hundreds of people sitting around filling out dozens of different kinds of bills for dozens of insurance companies." Maybe, but the prospect of overhauling our system this way, displacing all the private insurers and other infrastructure after all these decades, isn't likely. For there would be one group of losers — and these losers have lots of clout. They're the health care providers like hospitals and CT-scan-equipment makers whose profits — embedded in the bills we have examined — would be sacrificed. They would suffer because of the lower prices Medicare would pay them when the patient is 64, compared with what they are able to charge when that patient is either covered by private insurance or has no insurance at all.

That kind of systemic overhaul not only seems unrealistic but is also packed with all kinds of risk related to the microproblems of execution and the macro issue of giving government all that power.

Yet while Medicare may not be a realistic systemwide model for reform, the way Medicare works does demonstrate, by comparison, how the overall health care market doesn't work.

Unless you are protected by Medicare, the health care market is not a market at all. It's a crapshoot. People fare differently according to circumstances they can neither control nor predict. They may have no insurance. They may have insurance, but their employer chooses their insurance plan and it may have a payout limit or not cover a drug or treatment they need. They may or may not be old enough to be on Medicare or, given the different standards of the 50 states, be poor enough to be on Medicaid. If they're not protected by Medicare or they're protected only partly by private insurance with high co-pays, they have little visibility into pricing, let alone control of it. They have little choice of hospitals or the services they are billed for, even if they somehow know the prices before they get billed for the services. They have no idea what their bills mean, and those who maintain the chargemasters couldn't explain them if they wanted to. How much of the bills they end up paying may depend on the generosity of the hospital or on whether they happen to get the help of a billing advocate. They have no choice of the drugs that they have to buy or the lab tests or CT scans that they have to get, and they would not know what to do if they did have a choice. They are powerless buyers in a seller's market where the only sure thing is the profit of the sellers.

Indeed, the only player in the system that seems to have to balance countervailing interests the way market players in a real market usually do is Medicare. It has to answer to Congress and the taxpayers for wasting money, and it has to answer to portions of the same groups for trying to hold on to money it shouldn't. Hospitals, drug companies and other suppliers, even the insurance companies, don't have those worries.

Moreover, the only players in the private sector who seem to operate efficiently are the private contractors working — dare I say it? — under the government's supervision. They're the Medicare claims processors that handle claims like Alan A.'s for 84¢ each. With these and all other Medicare costs added together, Medicare's total management, administrative and processing expenses are about $3.8 billion for processing more than a billion claims a year worth $550 billion. That's an overall administrative and management cost of about two-thirds of 1% of the amount of the claims, or less than $3.80 per claim. According to its latest SEC filing, Aetna spent $6.9 billion on operating expenses (including claims processing, accounting, sales and executive management) in 2012. That's about $30 for each of the 229 million claims Aetna processed, and it amounts to about 29% of the $23.7 billion Aetna pays out in claims.

The real issue isn't whether we have a single payer or multiple payers. It's whether whoever pays has a fair chance in a fair market. Congress has given Medicare that power when it comes to dealing with hospitals and doctors, and we have seen how that works to drive down the prices Medicare pays, just as we've seen what happens when Congress handcuffs Medicare when it comes to evaluating and buying drugs, medical devices and equipment. Stripping away what is now the sellers' overwhelming leverage in dealing with Medicare in those areas and with private payers in all aspects of the market would inject fairness into the market. We don't have to scrap our system and aren't likely to. But we can reduce the $750 billion that we overspend on health care in the U.S. in part by acknowledging what other countries have: because the health care market deals in a life-or-death product, it cannot be left to its own devices.

Put simply, the bills tell us that this is not about interfering in a free market. It's about facing the reality that our largest consumer product by far — one-fifth of our economy — does not operate in a free market.

So how can we fix it?

Changing Our Choices We should tighten antitrust laws related to hospitals to keep them from becoming so dominant in a region that insurance companies are helpless in negotiating prices with them. The hospitals' continuing consolidation of both lab work and doctors' practices is one reason that trying to cut the deficit by simply lowering the fees Medicare and Medicaid pay to hospitals will not work. It will only cause the hospitals to shift the costs to non-Medicare patients in order to maintain profits — which they will be able to do because of their increasing leverage in their markets over insurers. Insurance premiums will therefore go up — which in turn will drive the deficit back up, because the subsidies on insurance premiums that Obamacare will soon offer to those who cannot afford them will have to go up.

Similarly, we should tax hospital profits at 75% and have a tax surcharge on all nondoctor hospital salaries that exceed, say, $750,000. Why are high profits at hospitals regarded as a given that we have to work around? Why shouldn't those who are profiting the most from a market whose costs are victimizing everyone else chip in to help? If we recouped 75% of all hospital profits (from nonprofit as well as for-profit institutions), that would save over $80 billion a year before counting what we would save on tests that hospitals might not perform if their profit incentives were shaved.

To be sure, this too seems unlikely to happen. Hospitals may be the most politically powerful institution in any congressional district. They're usually admired as their community's most important charitable institution, and their influential stakeholders run the gamut from equipment makers to drug companies to doctors to thousands of rank-and-file employees. Then again, if every community paid more attention to those administrator salaries, to those nonprofits' profit margins and to charges like $77 for gauze pads, perhaps the political balance would shift.

We should outlaw the chargemaster. Everyone involved, except a patient who gets a bill based on one (or worse, gets sued on the basis of one), shrugs off chargemasters as a fiction. So why not require that they be rewritten to reflect a process that considers actual and thoroughly transparent costs? After all, hospitals are supposed to be government-sanctioned institutions accountable to the public. Hospitals love the chargemaster because it gives them a big number to put in front of rich uninsured patients (typically from outside the U.S.) or, as is more likely, to attach to lawsuits or give to bill collectors, establishing a place from which they can negotiate settlements. It's also a great place from which to start negotiations with insurance companies, which also love the chargemaster because they can then make their customers feel good when they get an Explanation of Benefits that shows the terrific discounts their insurance company won for them.

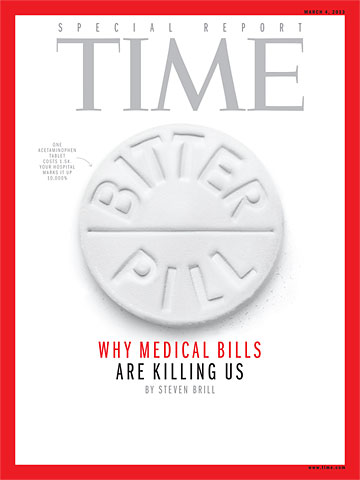

But for patients, the chargemasters are both the real and the metaphoric essence of the broken market. They are anything but irrelevant. They're the source of the poison coursing through the health care ecosystem.

We should amend patent laws so that makers of wonder drugs would be limited in how they can exploit the monopoly our patent laws give them. Or we could simply set price limits or profit-margin caps on these drugs. Why are the drug profit margins treated as another given that we have to work around to get out of the $750 billion annual overspend, rather than a problem to be solved?

Just bringing these overall profits down to those of the software industry would save billions of dollars. Reducing drugmakers' prices to what they get in other developed countries would save over $90 billion a year. It could save Medicare — meaning the taxpayers — more than $25 billion a year, or $250 billion over 10 years. Depending on whether that $250 billion is compared with the Republican or Democratic deficit-cutting proposals, that's a third or a half of the Medicare cuts now being talked about.

Similarly, we should tighten what Medicare pays for CT or MRI tests a lot more and even cap what insurance companies can pay for them. This is a huge contributor to our massive overspending on outpatient costs. And we should cap profits on lab tests done in-house by hospitals or doctors.

Finally, we should embarrass Democrats into stopping their fight against medical-malpractice reform and instead provide safe-harbor defenses for doctors so they don't have to order a CT scan whenever, as one hospital administrator put it, someone in the emergency room says the word head. Trial lawyers who make their bread and butter from civil suits have been the Democrats' biggest financial backer for decades. Republicans are right when they argue that tort reform is overdue. Eliminating the rationale or excuse for all the extra doctor exams, lab tests and use of CT scans and MRIs could cut tens of billions of dollars a year while drastically cutting what hospitals and doctors spend on malpractice insurance and pass along to patients.

Other options are more tongue in cheek, though they illustrate the absurdity of the hole we have fallen into. We could limit administrator salaries at hospitals to five or six times what the lowest-paid licensed physician gets for caring for patients there. That might take care of the self-fulfilling peer dynamic that Gunn of Sloan-Kettering cited when he explained, "We all use the same compensation consultants." Then again, it might unleash a wave of salary increases for junior doctors.

Or we could require drug companies to include a prominent, plain-English notice of the gross profit margin on the packaging of each drug, as well as the salary of the parent company's CEO. The same would have to be posted on the company's website. If nothing else, it would be a good test of embarrassment thresholds.

None of these suggestions will come as a revelation to the policy experts who put together Obamacare or to those before them who pushed health care reform for decades. They know what the core problem is — lopsided pricing and outsize profits in a market that doesn't work. Yet there is little in Obamacare that addresses that core issue or jeopardizes the paydays of those thriving in that marketplace. In fact, by bringing so many new customers into that market by mandating that they get health insurance and then providing taxpayer support to pay their insurance premiums, Obamacare enriches them. That, of course, is why the bill was able to get through Congress.

Obamacare does some good work around the edges of the core problem. It restricts abusive hospital-bill collecting. It forces insurers to provide explanations of their policies in plain English. It requires a more rigorous appeal process conducted by independent entities when insurance coverage is denied. These are all positive changes, as is putting the insurance umbrella over tens of millions more Americans — a historic breakthrough. But none of it is a path to bending the health care cost curve. Indeed, while Obamacare's promotion of statewide insurance exchanges may help distribute health-insurance policies to individuals now frozen out of the market, those exchanges could raise costs, not lower them. With hospitals consolidating by buying doctors' practices and competing hospitals, their leverage over insurance companies is increasing. That's a trend that will only be accelerated if there are more insurance companies with less market share competing in a new exchange market trying to negotiate with a dominant hospital and its doctors. Similarly, higher insurance premiums — much of them paid by taxpayers through Obamacare's subsidies for those who can't afford insurance but now must buy it — will certainly be the result of three of Obamacare's best provisions: the prohibitions on exclusions for pre-existing conditions, the restrictions on co-pays for preventive care and the end of annual or lifetime payout caps.

Put simply, with Obamacare we've changed the rules related to who pays for what, but we haven't done much to change the prices we pay.

When you follow the money, you see the choices we've made, knowingly or unknowingly.

Over the past few decades, we've enriched the labs, drug companies, medical device makers, hospital administrators and purveyors of CT scans, MRIs, canes and wheelchairs. Meanwhile, we've squeezed the doctors who don't own their own clinics, don't work as drug or device consultants or don't otherwise game a system that is so gameable. And of course, we've squeezed everyone outside the system who gets stuck with the bills.

We've created a secure, prosperous island in an economy that is suffering under the weight of the riches those on the island extract.

And we've allowed those on the island and their lobbyists and allies to control the debate, diverting us from what Gerard Anderson, a health care economist at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, says is the obvious and only issue: "All the prices are too damn high."

Brill, the author of Class Warfare: Inside the Fight to Fix America’s Schools, is the founder of Court TV and the American Lawyer