(10 of 11)

This does not mean the system is airtight. If anything, all that recovery activity suggests fallibility, even as it suggests more buttoned-up operations than those run by private insurers, whose payment systems are notoriously erratic.

Too Much Health Care? In a review of other bills of those enrolled in Medicare, a pattern of deep, deep discounting of chargemaster charges emerged that mirrored how Alan A.'s bills were shrunk down to reality. A $121,414 Stanford Hospital bill for a 90-year-old California woman who fell and broke her wrist became $16,949. A $51,445 bill for the three days an ailing 91-year-old spent getting tests and being sedated in the hospital before dying of old age became $19,242. Before Medicare went to work, the bill was chock-full of creative chargemaster charges from the California Pacific Medical Center — part of Sutter Health, a dominant nonprofit Northern California chain whose CEO made $5,241,305 in 2011.

Another pattern emerged from a look at these bills: some seniors apparently visit doctors almost weekly or even daily, for all varieties of ailments. Sure, as patients age they are increasingly in need of medical care. But at least some of the time, the fact that they pay almost nothing to spend their days in doctors' offices must also be a factor, especially if they have the supplemental insurance that covers most of the 20% not covered by Medicare.

Alan A. is now 89, and the mound of bills and Medicare statements he showed me for 2011 — when he had his heart attack and continued his treatments at Sloan-Kettering — seemed to add up to about $350,000, although I could not tell for sure because a few of the smaller ones may have been duplicates. What is certain — because his insurance company tallied it for him in a year-end statement — was that his total out-of-pocket expense was $1,139, or less than 0.2% of his overall medical bills. Those bills included what seemed to be 33 visits in one year to 11 doctors who had nothing to do with his recovery from the heart attack or his cancer. In all cases, he was routinely asked to pay almost nothing: $2.20 for a check of a sinus problem, $1.70 for an eye exam, 33¢ to deal with a bunion. When he showed me those bills he chuckled.

A comfortable member of the middle class, Alan A. could easily afford the burden of higher co-pays that would encourage him to use doctors less casually or would at least stick taxpayers with less of the bill if he wants to get that bunion treated. AARP (formerly the American Association of Retired Persons) and other liberal entitlement lobbies oppose these types of changes and consistently distort the arithmetic around them. But it seems clear that Medicare could save billions of dollars if it required that no Medicare supplemental-insurance plan for people with certain income or asset levels could result in their paying less than, say, 10% of a doctor's bill until they had paid $2,000 or $3,000 out of their pockets in total bills in a year. (The AARP might oppose this idea for another reason: it gets royalties from UnitedHealthcare for endorsing United's supplemental-insurance product.)

Medicare spent more than $6.5 billion last year to pay doctors (even at the discounted Medicare rates) for the service codes that denote the most basic categories of office visits. By asking people like Alan A. to pay more than a negligible share, Medicare could recoup $1 billion to $2 billion of those costs yearly.

Too Much Doctoring? Another doctor's bill, for which Alan A.'s share was 19¢, suggests a second apparent flaw in the system. This was one of 50 bills from 26 doctors who saw Alan A. at Virtua Marlton hospital or at the ManorCare convalescent center after his heart attack or read one of his diagnostic tests at the two facilities. "They paraded in once a day or once every other day, looked at me and poked around a bit and left," Alan A. recalls. Other than the doctor in charge of his heart-attack recovery, "I had no idea who they were until I got these bills. But for a dollar or two, so what?"

The "so what," of course, is that although Medicare deeply discounted the bills, it — meaning taxpayers — still paid from $7.48 (for a chest X-ray reading) to $164 for each encounter.

"One of the benefits attending physicians get from many hospitals is the opportunity to cruise the halls and go into a Medicare patient's room and rack up a few dollars," says a doctor who has worked at several hospitals across the country. "In some places it's a Monday-morning tradition. You go see the people who came in over the weekend. There's always an ostensible reason, but there's also a lot of abuse."

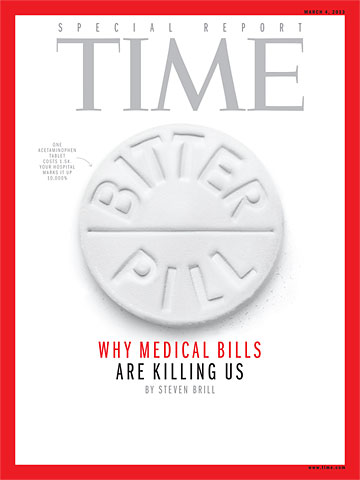

Photograph by Nick Veasey for TIME

Sodium Chloride $84 Hospital charge for standard saline solution. Online, a liter bag costs $5.16

When health care wonks focus on this kind of overdoctoring, they complain (and write endless essays) about what they call the fee-for-service mode, meaning that doctors mostly get paid for the time they spend treating patients or ordering and reading tests. Alan A. didn't care how much time his cancer or heart doctor spent with him or how many tests he got. He cared only that he got better.

Some private care organizations have made progress in avoiding this overdoctoring by paying salaries to their physicians and giving them incentives based on patient outcomes. Medicare and private insurers have yet to find a way to do that with doctors, nor are they likely to, given the current structure that involves hundreds of thousands of private providers billing them for their services.

In passing Obamacare, Congress enabled Medicare to drive efficiencies in hospital care based on the notion that good care should be rewarded and the opposite penalized. The primary lever is a system of penalties Obamacare imposes on hospitals for bad care — a term defined as unacceptable rates of adverse events, such as infections or injuries during a patient's hospital stay or readmissions within a month after discharge. Both kinds of adverse events are more common than you might think: 1 in 5 Medicare patients is readmitted within 30 days, for example. One Medicare report asserts that "Medicare spent an estimated $4.4 billion in 2009 to care for patients who had been harmed in the hospital, and readmissions cost Medicare another $26 billion." The anticipated savings that will be produced by the threat of these new penalties are what has allowed the Obama Administration to claim that Obamacare can cut hundreds of billions of dollars from Medicare over the next 10 years without shortchanging beneficiaries. "These payment penalties are sending a shock through the system that will drive costs down," says Blum, the deputy administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

There are lots of other shocks Blum and his colleagues would like to send. However, Congress won't allow him to. Chief among them, as we have seen, would be allowing Medicare, the world's largest buyer of prescription drugs, to negotiate the prices that it pays for them and to make purchasing decisions on the basis of comparative effectiveness. But there's also the cane that Alan A. got after his heart attack. Medicare paid $21.97 for it. Alan A. could have bought it on Amazon for about $12. Other than in a few pilot regions that Congress designated in 2011 after a push by the Obama Administration, Congress has not allowed Medicare to drive down the price of any so-called durable medical equipment through competitive bidding.

This is more than a matter of the 124,000 canes Medicare reports that it buys every year. It's about mail-order diabetic supplies, wheelchairs, home medical beds and personal oxygen supplies too. Medicare spends about $15 billion annually for these goods.

In the areas of the country where Medicare has been allowed by Congress to conduct a competitive-bidding pilot program, the process has produced savings of 40%. But so far, the pilot programs cover only about 3% of the medical goods seniors typically use. Taking the program nationwide and saving 40% of the entire $15 billion would mean saving $6 billion a year for taxpayers.

The Way Out Of the Sinkhole "I was driving through central Florida a year or two ago," says Medicare's Blum. "And it seemed like every billboard I saw advertised some hospital with these big shiny buildings or showed some new wing of a hospital being constructed ... So when you tell me that the hospitals say they are losing money on Medicare and shifting costs from Medicare patients to other patients, my reaction is that Central Florida is overflowing with Medicare patients and all those hospitals are expanding and advertising for Medicare patients. So you can't tell me they're losing money ... Hospitals don't lose money when they serve Medicare patients."

If that's the case, I asked, why not just extend the program to everyone and pay for it all by charging people under 65 the kinds of premiums they would pay to private insurance companies? "That's not for me to say," Blum replied.

In the debate over controlling Medicare costs, politicians from both parties continue to suggest that Congress raise the age of eligibility for Medicare from 65 to 67. Doing so, they argue, would save the government tens of billions of dollars a year. So it's worth noting another detail about the case of Janice S., which we examined earlier. Had she felt those chest pains and gone to the Stamford Hospital emergency room a month later, she would have been on Medicare, because she would have just celebrated her 65th birthday.

If covered by Medicare, Janice S.'s $21,000 bill would have been deeply discounted and, as is standard, Medicare would have picked up 80% of the reduced cost. The bottom line is that Janice S. would probably have ended up paying $500 to $600 for her 20% share of her heart-attack scare. And she would have paid only a fraction of that — maybe $100 — if, like most Medicare beneficiaries, she had paid for supplemental insurance to cover most of that 20%.

In fact, those numbers would seem to argue for lowering the Medicare age, not raising it — and not just from Janice S.'s standpoint but also from the taxpayers' side of the equation. That's not a liberal argument for protecting entitlements while the deficit balloons. It's just a matter of hardheaded arithmetic.

As currently constituted, Obamacare is going to require people like Janice S. to get private insurance coverage and will subsidize those who can't afford it. But the cost of that private insurance — and therefore those subsidies — will be much higher than if the same people were enrolled in Medicare at an earlier age. That's because Medicare buys health care services at much lower rates than any insurance company. Thus the best way both to lower the deficit and to help save money for people like Janice S. would seem to be to bring her and other near seniors into the Medicare system before they reach 65. They could be required to pay premiums based on their incomes, with the poor paying low premiums and the better off paying what they might have paid a private insurer. Those who can afford it might also be required to pay a higher proportion of their bills — say, 25% or 30% — rather than the 20% they're now required to pay for outpatient bills.

Meanwhile, adding younger people like Janice S. would lower the overall cost per beneficiary to Medicare and help cut its deficit still more, because younger members are likelier to be healthier.

From Janice S.'s standpoint, whatever premium she would pay for this age-64 Medicare protection would still be less than what she had been paying under the COBRA plan that she wished she could have kept after the rules dictated that she be cut off after she lost her job.

The only way this would not work is if 64-year-olds started using health care services they didn't need. They might be tempted to, because, as we saw with Alan A., Medicare's protection is so broad and supplemental private insurance costs so little that it all but eliminates patients' obligation to pay the 20% of outpatient-care costs that Medicare doesn't cover. To deal with that, a provision could be added requiring that 64-year-olds taking advantage of Medicare could not buy insurance freeing them from more than, say, 5% or 10% of their responsibility for the bills, with the percentage set according to their wealth. It would be a similar, though more stringent, provision of the kind I've already suggested for current Medicare beneficiaries as a way to cut the cost of people overusing benefits.

If that logic applies to 64-year-olds, then it would seem to apply even more readily to healthier 40-year-olds or 18-year-olds. This is the single-payer approach favored by liberals and used by most developed countries.

Then again, however much hospitals might survive or struggle under that scenario, no doctor could hope for anything approaching the income he or she deserves (and that will make future doctors want to practice) if 100% of their patients yielded anything close to the low rates Medicare pays.