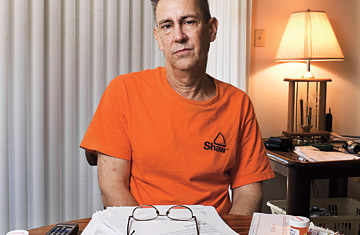

Patrick Tumulty with his medication and his bills.

(6 of 7)

As this country prepares to engage in its first serious debate over comprehensive health-care reform in 15 years, there are two leading approaches to covering the 45 million uninsured and reining in costs. One, which President Barack Obama is putting forward, would force more employers to offer coverage to their workers, with subsidies and other incentives to make it more affordable. The other, advocated by Republicans (including Senator John McCain in the recent presidential campaign), would take away some of the tax advantages that come with getting coverage at work and thereby put many Americans who are now covered by their employers into the marketplace on their own. The idea is that they would be the ones best equipped to decide which plan suits their individual needs.

Pat's experience suggests it is difficult for an individual to make such judgments. And the existing market for these kinds of policies leaves a lot to be desired. A 2006 Commonwealth Fund study found that only 1 in 10 people who shopped for insurance in the individual market ended up buying a policy. Most of the others couldn't find the coverage they needed at a price they could afford.

The individual health-care consumer has very little power or information. Still, it turns out that there are ways to fight back. As I was reporting my brother's story, I discovered something about Pat's former insurance company: last May, insurance regulators in Connecticut imposed a record $2.1 million in penalties on two Assurant subsidiaries for allegedly engaging unfairly in a practice called postclaims underwriting--combing through short-term policyholders' medical records to find pretexts to deny their claims or rescind their policies. In one case, a woman whose non-Hodgkin's lymphoma was diagnosed in 2005 was denied coverage because she had told her doctor on a previous visit that she was feeling tired. Assurant agreed to pay the fine but admitted no wrongdoing.

So I contacted the Texas Department of Insurance, identifying myself as both the sister of an aggrieved policyholder and a journalist. Officials there suggested that Pat file a complaint against the company. Each year the department receives as many as 11,000 complaints and manages to get $12 million to $13 million back for consumers, Audrey Selden, the department's consumer-protection chief, told me. "It is important to complain."

And it's easy too. It took Pat and me less than 10 minutes to fill out the complaint form over the Internet. That was Jan. 14, 2009. On Feb. 9, we had an answer: Assurant maintained that it had done nothing wrong and that Pat should never have relied on short-term coverage over a long period. But given "the extraordinary circumstances involved," the company agreed to pay his claims from last year, when the policy was still in force. (Pat canceled it on Aug. 22, 2008.) Those extraordinary circumstances, I assume, included the fact that the state insurance department was sniffing around.