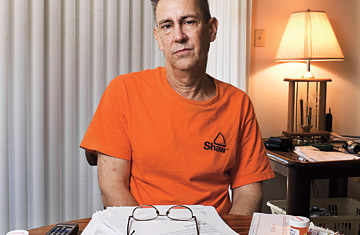

Patrick Tumulty with his medication and his bills.

(5 of 7)

There's another paradox: if Pat gets sick enough to need dialysis, as he well may, the Federal Government will pick up those staggering costs under the Medicare program for end-stage renal disease. But until that point is reached--and the goal is to keep him from getting there--his options are limited. Now that he is sick, it would be nearly impossible for him to purchase another insurance policy on the individual market. Since he lives independently and holds a job, it would be difficult for him to qualify for Social Security disability benefits. While Texas, like 34 other states, has a high-risk pool for those who are hard to insure, the program is twice as expensive as an average individual health-insurance policy. And my brother would have to wait 12 months to join with a pre-existing condition, under the state's "adverse selection" regulations that seek to prevent uninsured people from joining the pool only after they get sick.

As we were running out of options, Smith told us there was one more avenue to try. Bexar County--where San Antonio is located and an estimated 30% of people under 65 do not have health coverage--has a health-care program for the uninsured that is far more generous than most in Texas and practically unique in the country. Rather than continuing to wait for the uninsured to show up in its emergency rooms, in 1997 the Bexar County hospital district established a system called CareLink for those who make 200% of the poverty line or less. (In his current job, answering queries that come in to a text-message information service, Pat earns $1,257 a month, which means he qualifies.)

CareLink operates much like a health-maintenance organization for its 55,000 clients, negotiating prices with health-care providers and then billing clients on a sliding scale according to their income. (Pat's CareLink bills run around $40 a month.) And it puts a heavy emphasis on preventive care; on Pat's first examination at an austere CareLink clinic in northwestern San Antonio, he got tetanus and flu shots as part of the deal. Another stroke of good fortune: Pat's kidney doctor, Smolens, is a participating specialist with CareLink.

For primary care, CareLink assigned Pat to Dr. Carolyn Eaton, an engaging woman who has been working with the system for about a year. What alarms her most about the new patients she has seen lately, Eaton says, is how long people wait--diabetics whose feet are numb, cancer patients already in the advanced stages of the disease--before they seek treatment. "When people fall on hard times, they're kind of embarrassed," Eaton says. "Their health care ends up becoming much more expensive."

It's not a seamless system. Pat gets confused navigating between Smolens, who prescribes tests and medications, and CareLink, which must approve them. "The fact is, for guys like Pat, it requires a lot more work to do the same sorts of things" that would be a snap if he had insurance, says Smolens, sighing.

The Limits of Personal Choice