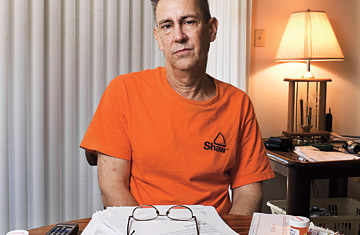

Patrick Tumulty with his medication and his bills.

(3 of 7)

What makes these cases terrifying, in addition to heartbreaking, is that they reveal the hard truth about this country's health-care system: just about anyone could be one bad diagnosis away from financial ruin. Most people get their coverage where they work. But Anna McCourt, a supervisor at the ACS call center, says employees often have difficulty understanding the jargon in insurance policies. Even human-resources personnel may not fully understand all the intricacies of a policy when briefing a new employee. Coverage that seems generous when you are healthy--eight annual doctor visits or three radiation courses--quickly proves insufficient if you find yourself really sick.

Between Coverage and Safety Net

Pat's decision to save some money by buying short-term insurance was a big mistake, says Karen Pollitz, project director of Georgetown University's Health Policy Institute and a leading expert on the individual-insurance market. "These short-term policies are a joke," she says. "Nobody should ever buy them. It is false security that is being sold. It's junk."

That's because diagnosing and treating an illness may not fall neatly into six-month increments. While Pat had been continuously covered since 2002 by the same company, Assurant Health, each successive policy treated him as a brand-new customer. In looking back over Pat's medical records, the company noticed test results from December, eight months earlier. Though Pat's doctors didn't determine the precise cause of the problem until the following July, his kidney disease was nonetheless judged a "pre-existing condition"--meaning his insurance wouldn't cover it, since he was now under a different six-month policy from the one he had when he got those first tests.

After 33 years of wrestling with insurance companies, Deborah Haile, payment coordinator at the San Antonio Kidney Disease Center, where Pat went for treatment, has pretty much figured out the system. So when I put in my first desperate call to her, on Aug. 20, 2008, she offered to make another run at Assurant. Within an hour, Haile called back, her voice bristling with anger. "Cancel that policy," she advised me. "Your brother is wasting his money on premiums, and he's going to need it."

There was at least one thing we didn't have to worry about, Haile assured me. Pat's kidney doctor, Peter Smolens, would keep treating him even if he couldn't pay. Smolens, a thin, soft-spoken man, later told me that about 10% of his patients have inadequate insurance or none at all. He has agonized with some as they struggled with hard choices, like whether to have a hospital biopsy or pay their mortgage. As a physician, he said, "you just see them. You know you're not going to get paid."