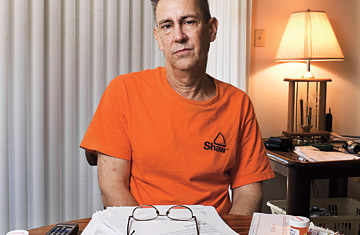

Patrick Tumulty with his medication and his bills.

(2 of 7)

The Underinsured

When we talk about health-care reform, we usually start with the problem of the roughly 45 million (and rising) uninsured Americans who have no health coverage at all. But Pat represents the shadow problem facing an additional 25 million people who spend more than 10% of their income on out-of-pocket medical costs. They are the underinsured, who may be all the more vulnerable because, until a health catastrophe hits, they're often blind to the danger they're in. In a 2005 Harvard University study of more than 1,700 bankruptcies across the country, researchers found that medical problems were behind half of them--and three-quarters of those bankrupt people actually had health insurance. As Elizabeth Warren, a Harvard Law professor who helped conduct the study, wrote in the Washington Post, "Nobody's safe ... A comfortable middle-class lifestyle? Good education? Decent job? No safeguards there. Most of the medically bankrupt were middle-class homeowners who had been to college and had responsible jobs--until illness struck."

If there is a ground zero for both problems, it is Texas, where I grew up and where my parents and brothers still live. About 1 in 4 Texans is uninsured, the highest rate in the country. The vast majority of the uninsured--8 in 10--live in households in which someone works, typically for a small business. But only 37% of Texas companies with fewer than 50 employees offer medical coverage.

The state's Medicaid program is notoriously stingy. State law requires counties to provide care only to those deemed "indigent," defined as people who earn less than 21% of the federal poverty line, or $2,274 a year for a single adult and $4,630 for a family of four. Many counties, particularly rural ones, do no more than that minimum. So Texas--a state with relatively little regulation of the health-insurance industry--is fertile territory for insurance companies selling bare-bones coverage at low prices.

But falling ill without adequate insurance leaves you at risk no matter where you live. Since 2005, the American Cancer Society (ACS) has maintained a national call center for cancer patients struggling with their bills. In that time, more than 21,000 people have called in asking for help. Every story is different, but the contours of the problem tend to be depressingly similar: the 10-year-old leukemia patient in Ohio who, after three rounds of chemotherapy and a bone-marrow transplant, had almost exhausted the maximum $1.5 million lifetime benefit allowed under her father's employer-provided plan; the Connecticut grocery-store worker who put off the radiation treatments for her Stage 2 breast cancer because she had used up her company plan's $20,000 annual maximum and was $18,000 in debt; the New Hampshire accountant who, unable to work during his treatment for Stage 3B stomach cancer, had to stop paying his mortgage to afford a $1,120 monthly premium for coverage with the state's high-risk insurance pool.