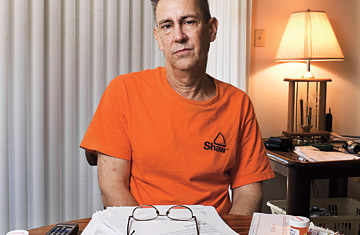

Patrick Tumulty with his medication and his bills.

(4 of 7)

As grateful as we were for Smolens' forbearance, that still left us with the question of how to keep up with the rapidly mounting bills for drugs and lab work. Haile put us in touch with B.J. Smith, a social worker at the center. Patient and reassuring, Smith turned out to be the angel we needed. She had only recently returned to work after taking off seven years to stay home with her two children. The first thing she advised Pat was to start paying his bills, all of them, even if it meant putting down only a few dollars a month on each one. Otherwise, everything he had--his one-bedroom condominium, 2003 Saturn Ion and $36,000 in savings--would be put at risk, as the letters from collection agencies had begun to arrive. Smith called Pat's medical creditors one by one and set up the arrangements: $51.89 a month to one hospital, $76 to another, installments of $4.78 a month to $111.89 a month on six different sets of LabCorp bills. Then there was the $626 he owed two radiologists. One agreed to knock off $22 as a hardship discount, writing Pat, "We are happy that we could be of assistance to you and your family in this time of need."

A paradox of medical costs is that people who can least afford them--the uninsured--end up being charged the most. Insurance companies, with large numbers of customers, have the financial muscle to negotiate low rates from health-care providers; individuals do not. Whereas insured patients would have been charged about $900 by the hospital that performed Pat's biopsy (and pay only a small fraction of that out of their own pocket), Pat's bill was $7,756. For lab work--and there was a lot of it--he was being charged as much as six times the price an insurance company would pay. One pathology lab's bill alone was $3,290.

Over time, with Smith's guidance, Pat learned to trim his bills here and there. Instead of refilling small prescriptions, for instance, he could buy some drugs more cheaply in bulk. (A hundred pills of one blood-pressure medication was less than $16 at Costco, compared with $200 at the pharmacy.) But that didn't address the cost of his care going forward. Pat's kidney function, which was 48% when Smolens first saw him last summer, has fallen to between 35% and 40%. And there are now outward, obvious signs of Pat's illness: he is lethargic, his eyes are puffy, and his lower legs and ankles are swollen to twice their normal size.

The disease--whose cause Pat's doctors doubt they will ever know--is winning. Now Smolens is trying to figure out whether Pat, whose Asperger's gives him a low tolerance for the demands of a complicated medical regimen, should move from his current medications to a more aggressive approach that includes immunosuppressing chemotherapy drugs. The newer drugs can cost $10,000 a treatment; even the old ones can easily run $500 a month. "It's almost like a black hole in terms of the potential costs," Smolens told me. "But when you look at the alternative--progressive kidney failure--then you're talking about having to receive dialysis, and the average cost of dialysis treatments in this country is $60,000 per year plus."