(9 of 11)

He got into law enforcement "kind of as an afterthought," he says. After earning a degree at Manhattan College, he and Powers enrolled together at New York University School of Law, and Giuliani ended up as a clerk to federal judge Lloyd MacMahon. The judge encouraged him to join the U.S. Attorney's office, and in 1970 Giuliani took his advice. Giuliani's ascent began in earnest three years after he arrived when, at 29, he was put in charge of the police-corruption cases springing from the Knapp Commission, an era romanticized in the book and movie Prince of the City. He did a stint in private practice and went to Washington for three years as the No. 3 man in Ronald Reagan's Justice Department. (All told, he has spent nine years of his career practicing law outside government.) In 1983 Giuliani was named U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York. By then his father had withered and died, a victim of prostate cancer. The last conversation Giuliani had with his father, he says, "was about courage and fear. I said to him, 'Were you ever afraid of anything?' He said to me, 'Always.' He said, 'Courage is being afraid but then doing what you have to do anyway.'"

The Real World

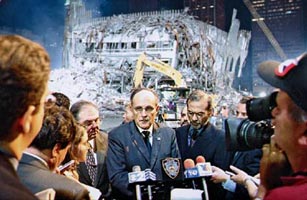

Giuliani's life reflected his dying father's words. Though the mayor's friend Peter Powers thinks Giuliani "was born without a fear gene," Rudy says it isn't so. On Sept. 11, when the first tower collapsed and he and his aides were stuck inside a building near the site, "there were times I was afraid. Everybody was. But the concentration was on. If I don't do what I have to do, everything falls apart." They tried to escape through the basement, but the doors were locked. "That's when I kept saying to myself, You've got to keep your head, and you've just got to keep thinking, What's the most sensible thing to do next? Something I learned a long time ago, also from my father, is that the more emotional things get, the calmer you have to become to figure your way out. Those things have become a matter of instinct for me at 57 years old. I didn't have to invent them."

When Giuliani hears people talking about how Americans have been living in "a different world" since Sept. 11, he disagrees. "We're not in a different world," he says. "It's the same world as before, except now we understand it better. The threat and danger were there, but now we recognize it. So it's probably a safer world now."

Giuliani understood the danger earlier than most. "I assumed from the time I came into office that New York City would be the subject of a terrorist attack," he says. The World Trade Center was bombed by Muslim terrorists in 1993, before he became mayor, and while most New Yorkers pushed the memory aside, Giuliani did not. To ease the long-standing disaster-scene turf battles between fire and police, he created the Office of Emergency Management and built a $13 million emergency command center on the 23rd floor of 7 World Trade Center, a mid-size building in the complex. The place was ridiculed as "Rudy's bunker." (Only the location was a mistake; on Sept. 11 the bunker had to be evacuated, and the entire building collapsed.) He beefed up security and restricted access around City Hall, brushing aside those who charged that he was stifling the democratic right to free assembly. He and his staff held drills playing out 10 disaster scenarios, from anthrax attacks to truck bombs to poison-gas releases.

He didn't foresee terrorists flying airliners into office towers, but the constant drilling ensured that when it happened, everyone in city government knew how to respond. "We used to make fun of those drills," says chief of staff Tony Carbonetti, "but I think they saved lives." In the weeks after Sept. 11 — but before spores started getting mailed to media targets around Manhattan — Giuliani convened meetings with the Centers for Disease Control and the fbi to discuss the threat of anthrax. As a result, he knew more about anthrax than Homeland Security chief Tom Ridge and Health and Human Services Secretary Tommy Thompson. While Ridge and Thompson contradicted each other and downplayed the lethal nature of the spores, Giuliani treated the public like grownups, offering unvarnished information and never having to backtrack. When he told people not to panic, they didn't.

Giuliani had his own issues with the Federal Government. The FBI was stingy with intelligence and slow to test for anthrax in the city. By late October, five New Yorkers had been infected with anthrax and one was dying. And on Monday, Oct. 29, the day before Giuliani's beloved Yankees were set to play Game 3 of the World Series at their stadium in the Bronx, Ridge and Attorney General John Ashcroft alerted the public to one of their "credible but unspecified" threats and advised local law enforcement to be on the highest level of alert. Giuliani phoned Ridge and asked what he was supposed to do with this warning. "Tom, the city is already on the very highest state of alert," he said. "The lampposts are on alert. I've got the World Series tomorrow night. I've got the President coming to throw out the first pitch. I've got 30,000 people running in the marathon on Sunday, with 2 million watching. Are you telling me to close the airports? Cancel the series? Tell the President not to come?" Ridge said he would call back. When he did, he told Giuliani to go ahead with all his plans.