(2 of 11)

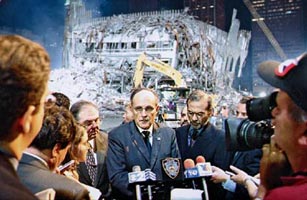

Fate had another idea. When the day of infamy came, Giuliani seized it as if he had been waiting for it all his life, taking on half a dozen critical roles and performing each masterfully. Improvising on the fly, he became America's homeland-security boss, giving calm, informative briefings about the attacks and the extraordinary response. He was the gutsy decision maker, balancing security against symbolism, overruling those who wanted to keep the city buttoned up tight, pushing key institutions — from the New York Stock Exchange to Major League Baseball — to reopen and prove that New Yorkers were getting on with life. He was the crisis manager, bringing together scores of major players from city, state and federal governments for marathon daily meetings that got everyone working together. And he was the consoler in chief, strong enough to let his voice brim with pain, compassion and love. When he said "the number of casualties will be more than any of us can bear," he showed a side of himself most people had never seen.

Giuliani's performance ensures that he will be remembered as the greatest mayor in the city's history, eclipsing even his hero, Fiorello La Guardia, who guided Gotham through the Great Depression. Giuliani's eloquence under fire has made him a global symbol of healing and defiance. World leaders from Vladimir Putin to Nelson Mandela to Tony Blair have come to New York to tour ground zero by his side. French President Jacques Chirac dubbed him "Rudy the Rock." As Jenkins, author of the biography that inspired Giuliani on the night of Sept. 11, told TIME, "What Giuliani succeeded in doing is what Churchill succeeded in doing in the dreadful summer of 1940: he managed to create an illusion that we were bound to win."

The Glorious Bluff

When he thinks about Churchill's wartime words, Giuliani now says, "I wonder how much of it was bluff." Three months to the day since the towers fell, he is riding with Time in his big tan SUV as it steers through the maze of cement barricades, switchbacks and checkpoints that lead into the heart of ground zero. "A lot of it had to be bluff," he says. "Churchill could not have known England was going to prevail. He hoped it, but there was no way he could know."

He is asked the obvious question: How much of his confidence on Sept. 11 was bluff?

"Some," he says matter-of-factly. "Look, in a crisis you have to be optimistic. When I said the spirit of the city would be stronger, I didn't know that. I just hoped it. There are parts of you that say, Maybe we're not going to get through this." He pauses. "You don't listen to them." He climbs out of the SUV and looks around. "It's still amazing," he says.

From here on West Street, inside the high fences and past the tourist throngs, ground zero looks like a huge, patriotic construction site — flags on the cranes, flags on the hard hats, flags on the huge white domes that house the mess hall and the EPA decontamination stalls. But your eye finds the last standing chunk of the north-tower facade (it would be removed in a few days) and the stump of twisted, melted steel that used to be 6 World Trade Center and the pit where corpses are still being recovered, and then the place looks like what it is — a mass grave. "This is the most emotional spot for me," Giuliani says, waving a hand in the street, "because this is where I was that morning." He points straight overhead, where the north tower used to be. "I looked up and saw a man jump out — above the fire, must have been at least 100 stories — and my eye followed him, almost transfixed, all the way down. He hit the top of that building," he says, pointing to what's left of 6 WTC. "Over there" — he gestures a few feet down the street — "is where the guys had their command post set up." The guys were the fire department's top brass: Chief of Department Pete Ganci, Commissioner Tommy Von Essen, First Deputy Commissioner Bill Feehan and Special Operations Chief Ray Downey. All except Von Essen are now dead. Giuliani takes three quick steps up the street. "I saw Father Judge here." Mychal Judge, the fire department chaplain, was heading toward the towers when he passed Giuliani. "I reached across and grabbed his hand and said what I always said to him, 'Pray for us, Father.' He smiled — he always had a big, confident smile — and said, 'I always do.' I followed him with my eyes, and he walked right down there." He points to the vanished north tower. Judge was killed by falling debris minutes later, either while administering last rites to a victim or immediately after. "You relive it," Giuliani says now. "You can't help but relive it."

"'Scuse me, Mayor, would you sign my hat?" The workman is extremely big, extremely dirty and just a little bit awestruck. He holds out a scuffed white hard hat, and Giuliani smiles. "I would love to," the mayor says, and by the time he has done so, 10 more guys with 10 more hats are waiting in line. It's like this everywhere Giuliani goes these days. The mayor, who leaves office Jan. 1, draws one long, loud thank-you from the people of his city. "Rudy, way to go!" calls Dwayne Dent, 37, an African-American ironworker. "You're about the greatest mayor ever, ain'tcha?" Giuliani gives him a melancholy smile. It's nice to be loved, but at times the cost is, as he predicted, more than he can bear.