(6 of 11)

With Donna Hanover and Giuliani's two children, Caroline, 12, and Andrew, 15, still living in Gracie Mansion, Nathan has been functioning as a kind of shadow First Lady — attending memorial services but not sitting with the mayor; keeping a low public profile while playing a significant role behind the scenes. She helped organize construction of the Family Center on Pier 94 in New York, leading 3,000 volunteers who, in just 36 hours, turned 125,000 sq. ft. of raw space into what she calls "a warm place where the survivors could grieve in dignity and get the help they needed."

Giuliani is now cancer free, and Nathan believes that God spared him so he would be able to lead on Sept. 11. The timing of his ordeals also makes the mayor think about God's hand. Had the terrorists struck one year earlier, "when I was going through daily radiation, I couldn't have done it." Had he not had the cancer, he probably would have stayed in the Senate race and might have won — and thus would not have been on the scene to help his city get through the crisis. And if not for the cancer, he says, "I would have dealt with Sept. 11 effectively, but not as effectively. I would not have been as peaceful about it."

Yet Giuliani still wrestles mightily with his faith, with the question of whether events happen randomly or according to a divine plan. "I'm not sure. I'm not sure. I really admire the widows who have this perfect, simple religious faith. I go back and forth about it. Sometimes I resolve it as destiny — it just happens, you have no control over it, there's no reason to get too afraid of it because you have to go ahead and do what you have to do. And then sometimes I have this feeling that it is part of God's plan, allowing us to work out who we are as human beings. He gives people the room to make choices like the ones the heroes made, the people that saved other people, or the evil choices that were also made."

He won't say he was "chosen" to lead the city at this moment. "Whatever my belief in God, I don't believe he enters into politics," he says. But the more he thinks about it, the more he accepts that "there must be some plan in all of it. Philosophically and theologically, the way I look at all of this is that if there are things beyond human rationality, then we're only going to have little glimpses of it. And as for my own personal odyssey, it worked out better for me and better for the city that all those things happened."

Monsignor Placa sums up the changes in his friend this way: "The cancer made him face his mortality. Sept. 11 made him face his immortality." Together the two pushed him to recognize that history forgets the petty fights but not the acts of true leadership — and that he should do the same. "I think Rudy's gotten the idea that what he does will either be part of the triviality that will be forgotten or else it will become part of the story of how a great people were able to deal with this."

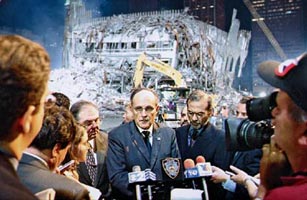

Giuliani has attended close to 200 funerals, services and wakes for police officers, fire fighters and emergency workers who died on Sept. 11, and each time he has offered a variation on the theme that "what could have destroyed us made us stronger," thanks to the heroes "who turned the worst attack on American soil into the most successful rescue operation in American history," with perhaps 20,000 civilian lives saved. At the police funerals, he points out that Sept. 11 succeeded in silencing the N.Y.P.D.'s critics and laments that it cost so many lives to do so. Giuliani had hoped to attend services for all 23 cops and 343 fire fighters lost that day, but that was impossible. He had felt that attending the services might help the survivors, show them how much the city honored their loss. He hadn't realized how much the funerals would help him.