(4 of 11)

Losing the Peace

In 1997 a haitian man named Abner Louima was sodomized with a mop handle by a cop in a Brooklyn-precinct bathroom. Two years later, an unarmed street peddler named Amadou Diallo was killed when police in the Bronx fired 41 shots at him in a dark vestibule. And a year after that, an unarmed security guard named Patrick Dorismond, who had been trying to hail a cab outside a midtown bar, was shot to death after a scuffle with undercover cops. Giuliani denounced the cops who brutalized Louima but defiantly backed those who killed Diallo and Dorismond. (In those cases, juries cleared the officers of wrongdoing.) After Dorismond was killed, Giuliani's instinct to defend the police led him to attack the unarmed victim; the mayor authorized release of Dorismond's juvenile records to "prove" his propensity for violence. The dead, Giuliani argued, waive their right to privacy. Even old friends and supporters were appalled. The man who had saved New York City saw his job-approval rating drop to 32%.

New York City was getting better, but the mayor seemed to be getting worse. When New York magazine launched an ad campaign calling itself "Possibly the only good thing in New York Rudy hasn't taken credit for," Giuliani had the ads yanked from the sides of city buses. The magazine sued and won. With the criminals on the run, the mayor was again resembling Churchill, a wartime leader too obstreperous to win the peace. Giuliani launched a "civility campaign" against jaywalkers, street vendors and noisy car alarms and a crusade against publicly funded art that offended his moral sensibilities. But the pose seemed hypocritical at best when Giuliani, whose wife had not been seen at City Hall in years, began making the rounds with Judi Nathan, a stylish New Yorker with wide, liquid eyes. The clash between the mayor's lifestyle and his policies became a pop-culture target, deftly skewered by Saturday Night Live comedian Tina Fey. "New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani is once again expressing his outrage at an art exhibit, this time at a painting in which Jesus is depicted as a naked woman," Fey deadpanned. "Said the mayor: 'This trash is not the sort of thing that I want to look at when I go to the museum with my mistress.'"

In the spring of 2000, Giuliani was edging toward a political move that he did not appear interested in making: running against Hillary Rodham Clinton for the Senate seat being vacated by Daniel Patrick Moynihan. That's when his carefully controlled, highly effective life went off the rails. He had been seeing Nathan since at least the previous year, but now the relationship exploded into the headlines. Donna Hanover later won a court order to prevent Nathan from attending city functions held at Gracie Mansion. Giuliani's divorce lawyer, Raoul Felder, counterattacked, calling Hanover an "uncaring mother" with "twisted motives." One of Giuliani's biographers, Village Voice reporter Wayne Barrett, broke the news of Giuliani's father's criminal past. Finally, in April 2000, Giuliani announced that he had received a diagnosis of prostate cancer, the disease that had killed his father. He withdrew from the Senate race and, with his handling of the Diallo and Dorismond cases still fresh in his mind, pledged to devote his remaining 18 months in office to breaking down "some of the barriers that maybe I placed" between him and minority communities. "I don't know exactly how you do that," he said, "but I'm going to try very hard."

The Barriers Fall

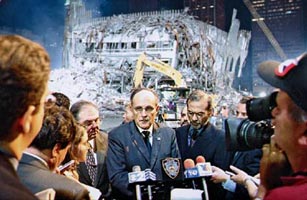

In the end it was Giuliani's performance on and after Sept. 11 that broke down those barriers, demonstrating once and for all how much he cared about New Yorkers, even if he had not always been able to show it. After Sept. 11, a good many Rudy watchers assumed he had changed — a rigid, self-righteous man had morphed into a big-hearted empath — but Giuliani's friends and aides say his warm side has always been there. Outsiders just couldn't see it. Countless times in the past eight years, he has sat at the bedside of an injured or dying cop or fire fighter, gently broken the awful news to the family, even remembered a widow's name years later. The public never saw these moments because the press was not there. Giuliani, so famously thirsty for attention, did away with the custom of holding mayoral press conferences at police funerals; he felt it was unseemly. "I've known him since he was 13. He's a hugger and a kisser. He always has been," says Monsignor Alan Placa, a Long Island cleric who remains one of the mayor's closest friends. "If the story is that he's changed, it's just the wrong story."

The story is how and why he was finally able to show the world what's inside him. It is now customary to say Sept. 11 put life into perspective and swept away the things that don't matter, and that is true for Giuliani. "All those little fights we have," he said six days after the towers fell, "they don't mean anything." That was a startling admission. Those "little fights" had defined his mayoralty. It was both inevitable and a bit sad that it took a disaster of this magnitude to bring out the best in him. Suddenly the whole world saw the New York City police and fire departments the way Giuliani had always seen them. And the whole world saw Giuliani the way only his closest friends had seen him. "I spent my first 7 3/4 years as mayor living out my father's advice that it's better to be respected than loved," he says. "But I had forgotten the last part of what he used to say: 'Eventually, you will love me.'"

The mayor has aged in the past year, but it suits him. His hair is grayer, thinner but still defiantly combed over. Small oval eyeglasses have softened his look; cancer and exploding skyscrapers have softened it more. "The whole experience continues to be very strange," he says one afternoon in his office at City Hall, where he is packing up eight years' worth of files, photos, baseball bats and Yankees caps, "because it is very personal, but it's also part of my public duty as mayor to deal with it."