(3 of 11)

The Old Rudy

"That is a moronic question," Giuliani hisses. "That is an absolutely moronic question." The mayor is standing in the street on a dusty hillside in Gilo, a West Jerusalem enclave where 21 Israelis have been hit by Palestinian mortar and sniper fire in the past 15 months. Giuliani is in Israel to show his support after the spate of suicide bombings — and to soak up adulation everywhere he goes — but right now he's sniping at a reporter who has just asked him whether he is frightened to be here. "Moronic!" the mayor repeats. The reporter says he has a right to ask the question. "And I have a right to point out that it is an absolutely moronic question!" Giuliani snaps. "If I were scared, I wouldn't be here." He stomps off.

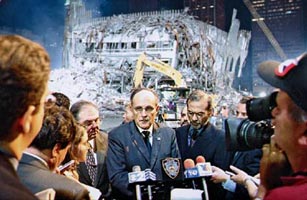

It's good to see the old Rudy again. All the grieving, all the gratitude, all the valedictory warmth that have been showering the mayor cannot obscure his pugilist's heart. The old Rudy resurfaced on Sept. 22, when Giuliani fired a counterterrorism specialist named Jerry Hauer — whom he had recruited just eight days earlier — because Hauer appeared at a press conference with a Democratic rival. The old Rudy showed up again on Oct. 11, when the mayor returned a $10 million check from Saudi Prince al-Waleed bin Talal, who had suggested that America should rethink its support for Israel. And he was seen frequently all that month as Giuliani made a bid to extend his term as mayor and slapped down those who questioned the purity of his motives. If he had found a way to get on the ballot, he would have won in a landslide. That's because Giuliani had saved New York twice: the first time, in the mid-1990s, through sheer toughness — asserting control over a crime-ridden city — and the second time, after Sept. 11, through a mix of toughness and soul. Each time, he gave the city the part of him it needed.

Giuliani has spent his adult life searching for missions impossible enough to suit his extravagant sense of self. A child of Brooklyn who was raised in a family of fire fighters, cops and criminals — five uncles in the uniformed services, an ex-con father and a Mob-connected uncle who ran a loan-sharking operation — he chose the path of righteousness and turned his life into a war against evil as he defined it. As a U.S. Attorney in New York during the 1980s, Giuliani was perhaps the most effective prosecutor in the country, locking up Mafia bosses, crooked politicians and Wall Street inside traders, though his vindictiveness and thirst for publicity led to troubling excesses. In 1987, for instance, his men arrested two stockbrokers in their offices, then handcuffed and perp-walked them past the TV cameras; later he quietly dropped the charges against them. But by 1993, when Giuliani made his second run for mayor — four years before, he lost to Democrat David Dinkins, the first African American to win the job — a tough prosecutor seemed to be just what the city needed. More than a million New Yorkers were on welfare, violent crime and crack cocaine had ravaged whole neighborhoods, and taxes and unemployment were sky-high. The squeegee pest was the city's mascot. The windows of parked cars were adorned with pathetic little signs that told thieves there was NO RADIO left to steal inside. It was fashionable to dismiss the place as ungovernable, and when candidate Giuliani gave speeches decrying that notion, he of course used Churchill to do it. Imagine, Giuliani said, if while the bombs were falling on London during the Battle of Britain, Churchill had said, "You know, this is really beyond our control. We can't do much about this." That, he argued, is what New York's leaders were doing: abdicating in the face of grave threats.

Candidate Giuliani eventually dropped the comparison because it seemed too dramatic, even to him. But after he defeated Dinkins, Mayor Giuliani made good on its implied promise. He did away with New York's traditional politics of soft and ineffectual symbolism — empathizing about problems but not fixing them — and got to work. His first police commissioner, William Bratton, came on the scene sounding like Churchill too. ("We will fight for every street. We will fight for every borough.") Using computer-mapping techniques to pinpoint crime hot spots, Bratton's N.Y.P.D. reduced serious crime by more than one-third and murder by almost half in just two years. But there was room in town for only one Churchill. Giuliani forced Bratton to resign, in large part because the commissioner hogged too many headlines. Giuliani felt vindicated when crime kept dropping like a stone under the loyalists he chose to succeed Bratton. And the public — shocked and delighted that the streets were actually safer and cleaner — didn't care how it happened. If Giuliani picked fights big and small, if he purged government of those he deemed insufficiently loyal, so be it. "People didn't elect me to be a conciliator. If they just wanted a nice guy, they would have stayed with Dinkins," Giuliani says now. "They wanted someone who was going to change this place. How do you expect me to change it if I don't fight with somebody? You don't change ingrained human behavior without confrontation, turmoil, anger."

He governed by hammering everyone else into submission, but in areas where that strategy was ineffective, such as reform of the city schools, he failed to make improvements. "The Boss," as his aides call him, inspired extraordinary loyalty and repaid it. He elevated a streetwise N.Y.P.D. detective named Bernard Kerik through the ranks of city government, eventually making him corrections commissioner and then police commissioner. Kerik, who compares entering Giuliani's inner circle to becoming "a made man in a Mafia family," reduced violence by 95% in the city jails and kept crime on the decline in New York this year even as it spiked around the country. "Nobody believed Giuliani had a heart," Kerik says. "He's not supposed to have a heart. He's an animal, he's obnoxious, he's arrogant. But you know what? He gets it done. Behind getting it done, he has a tremendously huge heart, but you're not going to succeed in New York City by being a sweetie. Giuliani has no gray areas — good or bad, right or wrong, end of story. That's the way he is. You don't like it, f___ you."

The city's black and Latino leaders did not like it. Focused on enforcing "one standard" for all New Yorkers (and obsessed with marginalizing activists like the Rev. Al Sharpton, whom Giuliani saw as a racial opportunist), Giuliani rarely reached out to any minority leaders. They complained that his aggressive cops were practicing racial profiling, stopping and frisking people because of their race. The Clinton Justice Department investigated the charge and decided not to bring a racial-discrimination case against the N.Y.P.D., but people believed their eyes, not the numbers. And though police shootings declined by 40% under Giuliani, minorities did not find comfort in that because of three awful brutality cases that, for many people, came to define the Giuliani years.