(6 of 6)

"There Aren't Easy Solutions"

But it's hard to tell in places like Dillon, where unemployment is now over 17%. Bernanke's childhood home went into foreclosure; his junior high is so dilapidated that Obama repeatedly cited it as a symbol of hard times after a 2008 campaign visit. A Dillon student was an honored guest at his first speech to Congress, but recently moved away after her mother lost her job as a welder.

Bernanke declared in September that the recession was ending, but he says it might feel like a recession for quite a while. Unemployment is a so-called lagging indicator, partly because beat-up businesses tend to be gun-shy about hiring after a downturn and partly because it takes modest growth just to absorb new workers and keep the jobless rate constant. The Fed is forecasting slightly stronger growth for the next few years, but it still expects 7% unemployment as late as 2012. "I shudder to think what the world would be like if Ben hadn't been running the Fed," former Secretary Paulson says. "It's just hard to explain that yes, we're in deep doo-doo, but we would have been in much deeper doo-doo."

Is there anything to be done? The Fed can't lower interest rates below zero, but liberals like New York Times columnist Paul Krugman — a Nobel-winning economist who was recruited to the Princeton faculty by Bernanke — are clamoring for even more action to rev the economy. At the same time, inflation hawks in the blogosphere, Congress and even the Fed's rate-setting committee are warning of new asset bubbles, soaring consumer prices and a collapse of the dollar if Bernanke doesn't reverse course and start tightening the money supply soon.

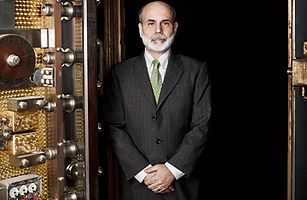

So here he is again, chatting in his grand office with the Rauschenberg on the wall and the economic ur-texts on the shelves. He chooses his words carefully. He knows they move markets. He's also awaiting confirmation by the Senate; socialist Bernie Sanders and ultraconservative Jim DeMint are both holding it up, so he doesn't want to make waves. But while he doesn't put it quite this bluntly, he implicitly makes a case for doing nothing, for waiting to see how the recovery plays out. He suggests that pumping more money into banks that are already flush with reserves could be like pushing on a string, increasing liquidity but not lending. For now, the Fed is merely instructing its supervisors to lend more. The days of whatever it takes are apparently over. "The additional steps aren't as obvious or clear as the ones we've already taken," Bernanke says. "It's an enormous problem. There aren't easy solutions."

Is he saying it's up to Congress to keep jamming on the accelerator with another fiscal stimulus? Well, no. Bernanke supported the $787 billion stimulus last winter, but when asked about a second, he repeatedly refused to bite, saying only that no matter what Congress does, it needs to produce a credible plan to reduce long-term deficits. Basically, he'd like us to make do with the money we've got — no additional borrowing or printing. What he wants Congress to do is reform the system so that big firms can be allowed to fail without risking an apocalypse.

Bernanke seems trapped by the psychology of the markets. He sees little evidence of rising prices, and he's clearly irritated by pundits who always seem to see inflation around the next corner, a mentality that reminds him of the misguided central bankers on his wall. And yet he knows he can't be seen as weak on inflation, any more than the Pentagon can be seen as weak on terrorism, because markets could go haywire. There's never been this much cash in the financial jet stream, and the Fed's virtual takeover of the mortgage-finance market will be tricky to unwind without spooking stock and real estate markets. Bernanke seems concerned that deeper deficits could rattle bond markets, pushing up long-term interest rates and potentially triggering a double-dip recession. He's got to worry about currency traders too; the Chinese and other holders of U.S. debt could lose confidence and start a run on the dollar that could shake up the world, or a Dubai-style default hysteria could start a run to the dollar that could cripple U.S. exports.

Meanwhile, the financial system remains vulnerable to another meltdown. The House passed a financial-reform bill on Dec. 11 without a single Republican vote, but action is not imminent in the bitterly divided Senate. So there is still no big-picture regulator to monitor systemic risk, and "too big to fail" firms are still free to use borrowed money to place wild bets with confidence that the government will ride to their rescue. Now they're lobbying frantically to block stronger capital requirements, leverage restrictions and other efforts to rein in their compulsive gambling.

Amazingly, the one reform that has attracted bipartisan support on Capitol Hill has been a crusade to rein in the Fed. The House passed a measure allowing congressional audits of monetary policy, which Bernanke believes would shatter the Fed's independence and immerse its rate-setting in politics. He's also fighting proposals to identify Fed borrowers, pointing out that during the Depression, borrowers turned down Reconstruction Finance Corporation dollars to avoid the stigma of disclosure. There is broad support for stripping the Fed of its consumer-protection functions, and the leading Senate bill would eliminate its regulatory functions as well. At his recent confirmation hearing, Bernanke endured hours of nitpicking and abuse. "Obviously, I haven't succeeded in defusing the political concerns about the Fed," Bernanke says with a wan smile.

Let's cut the guy some slack.

It's no consolation to the 1 in 6 Americans who is underemployed, the 1 in 7 homeowners with a delinquent mortgage or the 1 in 8 families on food stamps, but there would be far more joblessness, foreclosures and hunger were it not for Ben Bernanke. He didn't study economics to get rich — he and his wife still share a Ford Focus that's not quite paid off — and he didn't go to Washington to get a security detail. Instead, he truly believes the Keynesian notion that economists ought to be as useful as dentists. In a time of rabid partisanship, it's a tribute to Bernanke's basic desire to try to do the right thing that Obama aides don't seem worried about handing a Republican the keys to the economy for the next four years.

As the terrifying memories of free-falling markets fade, Bernanke has become a political victim of his apolitical success. His boldness in the crisis feels like yesterday's news. But if he's adopting a less aggressive approach to guiding a weak economy around skittish markets, it's not because he's timid, stupid or indifferent to Main Street. He's earned the benefit of the doubt. It's now up to our dysfunctional political system to let him do his job — and to fix the financial system so that he never has to save the world again.