(2 of 6)

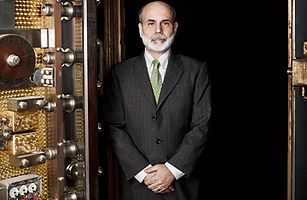

The Man from Main Street

Before George W. Bush brought him to Washington, Bernanke's only political experience was on his local school board. His friends didn't even know he was a Republican. His only leadership experience was chairing Princeton's economics department; he liked to joke that his major decisions involved what type of bagels to order for faculty meetings. Even after he took over the Fed, he never expected all this drama — which is to say he utterly failed to foresee the global financial implosion. But when credit markets disintegrated, he had the ideal background to respond. "It's like a novel," marvels Fed governor Daniel Tarullo. "It was the right man in the right place at the right time." It was as if his entire life had been preparation for this crisis.

Ben Bernanke was the smartest kid in Dillon, S.C., a small farming town on the Little Pee Dee River, which smelled like tobacco. His mother Edna was a teacher; his father Phil was a pharmacist. Ben inherited their love of learning. "He always wanted me to read to him," Edna recalls. "Then one day he said, Hey, I can read myself!' " He skipped first grade. He won the state spelling bee in sixth grade, though he botched edelweiss at the nationals in Washington, presumably because The Sound of Music hadn't made it to Dillon. In high school, he taught himself calculus.

It was the Depression that lured the family to Dillon. Phil's father Jonas Bernanke, an Austro-Hungarian army officer in World War I, had been struggling in the drugstore business in New York City after the stock-market crash of 1929. Credit was tight. Customers were broke. So when he saw an ad for a pharmacy for sale in Dillon, he decided to make a new start in the South. The Jay Bee Drug Co., named for his initials, became a local fixture, an old-fashioned family business on, yes, Main Street.

Today Bernanke tends to romanticize Dillon, emphasizing his Main Street middle-class roots. He says his summer jobs working construction at a hospital and waiting tables at the South of the Border tourist trap helped him appreciate working-class values. But as a kid, he couldn't wait to get out. "Me and Dillon," he sighs. "It's a funny psychodrama." The Bernankes were outsiders, an observant Jewish family in a tight-knit Christian community where social life revolved around church, running one of the few businesses that would extend credit to blacks. Dillon's schools were segregated until Bernanke's senior year, inspiring him to write a Remember the Titans–style novel about an integrated football team when he was a teenager. Once, his house was egged after he ate dinner with a black friend named Kenneth Manning at the local Shoney's.

Really, though, Bernanke wanted out of Dillon not because it was hostile but because it was confining. "It was a provincial Southern town, and anybody with any sense could see that Ben was unbelievably bright," says his old friend Manning, another restless intellect, who attended college and graduate school at Harvard and is now a professor at MIT. As a boy, Ben wrote poetry about a humble but clever snail who outwits a stuck-up rabbit. ("You shouldn't be so proud of speed. It's a very bad habit!") In a culture where the quarterback was king, Bernanke was an awkward geek who played alto sax in the marching band. It was Manning who showed the way out, telling him about Harvard, pestering him to apply. "I didn't want him to waste all that talent," Manning says.

At Harvard, Bernanke discovered that he could no longer get straight A's without studying; self-taught calculus was not ideal preparation for advanced mathematics. He ditched three majors — math, physics and English — before settling on economics. But he quickly became an academic star, eventually graduating summa cum laude and pursuing his doctorate at MIT. "He was substantially the same guy he is today — very quiet, very serious, very, very capable," recalls his MIT adviser, Stanley Fischer, who is now Israel's central banker. "He didn't try to do fancy or complex work just to show off. He wanted to answer real questions." Bernanke went on to teach at Stanford, then received tenure at Princeton when he was only 31, but he was never the kind of smart guy who needed to remind everyone how smart he was. "He came across as modest and unassuming then, and he still does," says Mervyn King, who had an office next to Bernanke's when they were young professors and is now Britain's central banker. "He's always been a scholar's scholar."

Bernanke's life as a scholar was fairly typical. He married a fellow bookworm, Anna, a teacher who is now planning a school for underprivileged kids in Maryland. They have two children, a son in medical school and a daughter who just finished college. Bernanke got sucked into academic politics, chairing his fractious department for six long years. Aside from his bagel-related responsibilities, he helped launch a center for finance studies, recruited top-notch economists and dissuaded them from bludgeoning one another. Anna even persuaded him to serve two terms on the school board, where he helped stop angry antitax activists from stripping funding for education. What was interesting about Bernanke's life as a scholar — especially considering what came next — was his scholarship.