(4 of 6)

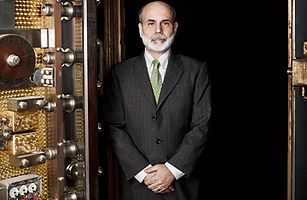

"Once He Got It, He Really Got It"

Bernanke became a Fed governor at the height of the Age of Greenspan, shortly after Bob Woodward's biography hailing the "Maestro" but before John McCain's quip that if Greenspan died, he should be propped up at the Fed like the corpse in Weekend at Bernie's. Bernanke quickly emerged as a staunch defender of the Greenspan Fed and its loose monetary policies. He suggested that raising interest rates to deflate the dotcom bubble before it popped would have been like using a sledgehammer to perform brain surgery. He delivered a call to arms against deflation, proposing ways the Fed could keep juicing the economy even if rates fell to zero. When he took over the Fed in 2006, after an uneventful eight-month White House stint leading Bush's Council of Economic Advisers, he said his top priority would be continuing Greenspan's policies. "Ben and I have never had a serious disagreement," Greenspan says.

In fact, Bernanke did make subtle changes, pushing for more transparency and clarity, speaking last instead of first at rate-setting meetings to avoid imposing his views. And while Greenspan had been laissez-faire about the Fed's oversight responsibilities, Bernanke pushed through long-overdue subprime-lending reforms in 2007. Still, Bernanke was as clueless as Greenspan about the coming storm. He dismissed warnings of a housing bubble. He insisted that economic fundamentals remained strong. In March 2007, he assured Congress that "the problems in the subprime market seem likely to be contained." The day before the global crisis erupted with a run on a French bank, the Fed was still saying its primary concern was inflation. "Bernanke had no idea what was going on," a foreign central banker tells TIME. "Once he got it, he really got it, and he acted swiftly and decisively. But wow! It took a while."

Bernanke concedes that he failed to anticipate how fragile such an overleveraged and interconnected system could be, how fear about a $1 trillion subprime mess could paralyze a $60 trillion global economy, how overnight-lending markets that got banks and corporations through the day could seize up overnight. He didn't share Greenspan's ideological faith that markets always know best, but he was surprised how spectacularly financial firms misjudged risk in their own portfolios, how collateralized debt obligations, credit-default swaps and other exotic financial weapons of mass destruction blew up in their faces. "None of us appreciated what a jury-rigged thing the financial system had become," he says. And while the Fed clearly blew its supervision of bank holding companies like Citigroup, it wasn't responsible for investment banks like Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers, the housing enterprises Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac or the other untraditional financial contraptions whose troubles drove the crisis. The Fed was not in charge of monitoring risks to the entire system either. No one was. "Of course there were things we could have done better," he says, "but this was a perfect storm."

Once Bernanke realized a disaster was unfolding, he made a conscious effort to project calm, even when he was working seven days a week and all hours of the night, even when the Wall Street types around him were screaming and cursing like stressed-out sailors. "He decided he wouldn't be a deer in the headlights and wouldn't let the world blow up," recalls Columbia University economist Frederic Mishkin, who was on the Fed board at the time. He also made a conscious decision to avoid the mistakes made by the bankers of the 1930s — not only their stingy refusals to supply cash but also their inflexible inside-the-box thinking. He hung their picture on his office wall. He held "blue sky" brainstorming sessions to solicit unorthodox ideas. An obscure legal provision gave the Fed broad latitude in "unusual and exigent circumstances," and he did whatever it took. "In exceptional circumstances," says European Central Bank president Jean-Claude Trichet, "he has done exceptional things."

"A War of Necessity"

Today the second-guessers are running wild. Why didn't the Fed stop bailed-out companies from handing out lucrative dividends and bonuses? Why pay off AIG's creditors in full? Why save Bear Stearns but not Lehman Brothers? "It's the price of success: people start to think you're omnipotent," Bernanke says. "We say we didn't have the authority, and it's Oh, you're the Fed. You could've come up with something.' "

The Fed has become the new Trilateral Commission; no conspiracy theory is too far-fetched. There's a vivid example on YouTube, a video titled "Florida Congressman Alan Grayson Laughs in Ben Bernanke's Face — Priceless!" The rabble-rousing Democrat, wearing a shiny tie festooned with dollar bills, grills Bernanke (and mispronounces his name) about $553 billion worth of currency swaps the Fed made with foreign central banks that ran low on dollars during the credit crunch. This was textbook central banking: pumping liquidity into markets during a panic. The swaps were safe, interest-bearing loans and didn't cost taxpayers a dime. But Grayson seems to think he's uncovered a nefarious handout to shadowy foreigners. The laughter comes after he sneers that the dollar rose 20% during these swaps and asks if that's a coincidence. Bernanke pauses, then replies, "Yes."