(5 of 6)

Ha-ha. Bernanke is right. The dollar strengthened because panicky investors were desperate for safe assets; that's why the swaps were so desperately needed. Unfortunately, YouTube doesn't provide Fed-to-English subtitles.

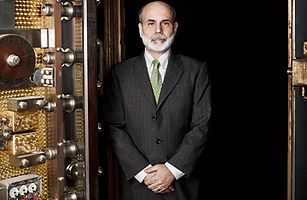

Bernanke has tried harder than any previous Fed chairman to explain his actions to the public, holding town-hall meetings, writing Op-Eds, even granting a few interviews. He has testified before Congress 13 times this year, and unlike the intentionally incomprehensible Greenspan, he has tried to be clear. But this is confusing stuff, and the Fed's by-any-means-necessary approach to the crisis has made it a juicy target. "We were the most aggressive central bank in the history of the world," says Fed governor and Bernanke confidant Kevin Warsh. The Fed used its magic money to shovel out more than $1.6 trillion worth of unconventional loans and is now buying over $1.7 trillion worth of unconventional assets. Here are some of the ways it has broken new ground:

The Zero Option. There was nothing unusual about lowering interest rates to boost a shaky economy, but in December 2008, Bernanke became the first Fed chairman to drop rates as low as they could go. "People always talk about central banks taking away the punch bowl, but when demand was falling so rapidly, Ben had to put the punch bowl on the table and say, Let's party!' " explains King, the governor of the Bank of England. A year later, rates remain near zero, for maximum monetary stimulus, and the Fed's rate-setting committee has signaled they will stay there for the foreseeable future.

Worldwide Outreach. Bernanke's pragmatic, plainspoken, data-driven approach has been a hit with his fellow central bankers, which has helped his efforts to forge a new global approach to global finance. "In our world, what counts are the fundamentals, and there's no show-off with him," Trichet says. Bernanke is in constant contact with Trichet, King and other key foreign players, and at one point he coordinated a six-nation rate cut to try to calm gyrating markets — another first.

The New Credit Channels. Bernanke has taken his research to heart, providing not just more money but targeted money, thawing out frozen credit markets and debuting seven blue-sky lending programs. When investors stopped buying the corporate paper that firms sell in overnight markets to meet their payroll, the Fed stepped in to buy it. When financing for securities backed by car loans, student loans, credit cards and mortgages dried up, the Fed opened new spigots to keep those markets open as well. This is one way the Fed's aid to Wall Street directly assisted Main Street, helping finance an estimated 3.3 million household loans, 100 million credit cards and 480,000 small-business loans. Bernanke took heat for substituting public for private credit, but it worked, because most of those private markets are functioning again. The emergency programs are all scheduled to wind down by June, and more than 80% of the loans have already been repaid, quietly returning billions of dollars in profits to taxpayers.

The Buying Binge. Bernanke wasn't kidding in 2002 when he claimed the Fed would still have ammunition to stimulate the economy if interest rates ever hit zero. This year he's gone on an astonishing shopping spree with conjured money, including a $1.25 trillion foray into mortgage-backed securities that represents an unprecedented intervention into a specific economic sector. The Fed has not only injected more liquidity into the economy but has directed it at the battered housing market, helping slash mortgage rates to their lowest levels since the 1940s. (The Bernankes recently refinanced their Capitol Hill townhouse after their adjustable-rate mortgage exploded, switching to a 30-year fixed rate of about 5%.) The Fed plans to stop buying next spring, but it's not clear when it will start thinning its bloated balance sheet.

The Rescue Missions. Bernanke has received the most attention — and flak — for his work with Paulson and Geithner to save financial giants from modern-day runs. The Fed financed a private takeover of Bear Stearns, assisted public takeovers of Fannie and Freddie, helped Bank of America swallow Merrill Lynch, tried unsuccessfully to prevent the globe-rattling demise of Lehman Brothers and engineered the epically distasteful bailout of the notorious AIG. Bernanke also helped lead the charge for the $700 billion Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), touting it as the only alternative to megadisaster.

None of this was pretty, and reasonable people can disagree about the judgment calls. The Fed is supposed to lend only against safe collateral; the Bear and AIG deals clearly crossed the Rubicon into risk. Letting Lehman fail nearly croaked the global economy. Saving AIG — an insurance company! — the next day seemed strangely inconsistent. Maybe the Fed could have devised a way to restrict bonuses at rescued firms while giving creditors haircuts. Maybe TARP could have required bailed-out banks to lend more. Certainly, all the interventions created moral hazard, sending a perverse message that "too big to fail" financial firms will be rescued no matter how badly they screw up, encouraging Wall Street traders to start gorging on risk again.

But that's what happens in panics when leaders actually try to preserve the financial system. The central bankers of the 1930s avoided moral hazard but betrayed the world. Bank runs are even scarier now that they don't require an actual run on an actual bank. Billions of dollars can be withdrawn with a keystroke, and all sorts of nonbank players are now dangerously intertwined with financial markets. Bernanke had to act, and it's not clear how the Fed could have saved Lehman without a buyer or administered haircuts to AIG's creditors without a bankruptcy judge. In June, Bernanke was savaged on Capitol Hill for supposedly pressuring Bank of America to buy Merrill; by December, Bank of America was healthy enough to repay its $45 billion in TARP aid. In fact, all but one of the 19 financial behemoths subjected to stress tests have received decent bills of health, and taxpayers are on track to profit from TARP's wildly unpopular bank bailouts. Bernanke says major financial crises generally cost nations 5% to 20% of their national output. This panic seems likely to cost the U.S. a fraction of 1%. "How much would you pay to avoid a second Depression?" he asks. "I mean, this is a pretty good return on investment."

Now that the fire is out, it's easy to attack the firefighters for getting the furniture wet or holding their hoses improperly. "The fire metaphor doesn't even do it. The Fed is more like the Pentagon," says Geithner. "It defends the freedom and security of Americans from existential threats ... This wasn't a war of choice. It was a war of necessity." And they won.