(3 of 6)

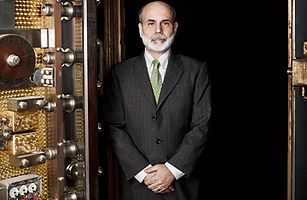

The Depression Buff

Bernanke says his first spark of interest in the Great Depression came as a boy listening to his mother's parents on their porch in Charlotte, N.C., where his grandfather was a kosher butcher. Their family had survived pogroms in Lithuania, but the story that captivated Bernanke involved a town full of shoe factories that closed during the Depression, leaving the community so poor that its children went barefoot. "I kept asking, Why didn't they just open the factories and make the kids shoes?' " he recalls. He would devote his career to questions like that.

Bernanke calls the Depression "the holy grail of macroeconomics," the ultimate intellectual challenge. To understand geology, he says, study earthquakes; to understand the economy, study the Depression. "I don't know why there aren't more Depression buffs," he wrote in a book of essays about the period. "The Depression was an incredibly dramatic episode — an era of stock-market crashes, breadlines, bank runs and wild currency speculation, with the storm clouds of war gathering ominously in the background ... For my money, few periods are so replete with human interest."

The first thing any Depression scholar comes to understand is that nothing — not hyperinflation, megadeficits or irked Chinese creditors — is as bad as a full-on Depression. A collapse in the "aggregate demand" for goods and services that makes an economy hum can be irreversible. Businesses fail, so workers lose jobs, so consumer spending declines, so more businesses fail. Depression scholars — including Bernanke — tend to see the Hoover Administration's approach of balancing budgets and tightening belts during the downturn as a tragic mistake. They embrace the Keynesian view that aggressive government action backed by government money is needed to reverse death spirals by restoring confidence and reviving demand. Get people money, and they can buy shoes for their barefoot kids, so shoe factories can reopen and rehire, which gets more people money. "People saw the Depression as a necessary thing — a chance to squeeze out the excesses, get back to Puritan morality," Bernanke says. "That just made things worse." In contrast, the Roosevelt Administration's New Deal stimulus and try-everything attitude made real, albeit uneven, progress against the downturn.

But Bernanke's main academic focus was the central role of monetary policy and the Fed in creating the catastrophe. So let's take a moment for a quick Fed primer. The Fed's central function is its dual mandate to steer the economy toward stable prices and maximum employment through monetary policy. To rev up a weak economy, it can lower interest rates by buying Treasury bonds or other safe securities, essentially printing money and dumping it into the banking system with a mouse click. Loose money can encourage banks to lend and firms to hire. This tends to make people happy but can increase inflation risks and weaken the dollar, which can make markets nervous and destroy the value of savings. Loose money can also provide the fuel for financial explosions by incentivizing wild risk-taking. Conversely, to apply brakes to an overheated economy and guard against inflation and asset bubbles, the Fed can raise interest rates by selling securities and contracting the money supply — as the saying goes, taking away the punch bowl as the party starts.

The Fed is also the nation's lender of last resort during financial panics, the original rationale for its creation in 1913. Traditional banks serve a vital economic function, providing safe places to park savings, then lending out the deposits so that borrowers can buy homes, start businesses and put the money to work. But banks are inherently vulnerable to breakdowns in confidence: when nervous depositors rush to withdraw their cash, even a solvent bank can run low on ready funds, which only intensifies the panic. After J.P. Morgan had to organize a private cash infusion to quell a 1907 panic, financiers persuaded Congress to create a central bank that could lend emergency money to stop runs, so that illiquid but otherwise healthy institutions wouldn't have to shut their doors.

Unfortunately, the Fed's leaders didn't comply after the Great Crash in 1929. Instead of lending freely, they let one-third of the nation's banks fail. Instead of lowering interest rates and expanding the money supply to spur the economy, they raised rates and tightened money, obsessing over inflation and the dollar's strength when they should have worried about deflation and runaway unemployment. Bernanke was deeply influenced by economist Milton Friedman's critiques of the Fed, and after joining its board in 2002, he apologized on its behalf at Friedman's 90th birthday party: "Regarding the Depression: You're right. We did it. But thanks to you, we won't do it again."

Bernanke's research added key nuances to the blame-the-Fed thesis. He showed that the Depression was caused not just by insufficient money sloshing around the system but also by clogged credit channels that prevented that money from flowing toward potentially productive borrowers when too many banks failed. He also outlined a "financial accelerator" effect in which disrupted financial markets increase the cost of credit, which intensifies downturns, which further increases the cost of credit. And he frequently explored the self-fulfilling nature of economic uncertainty, showing how it dissuades employers from hiring, consumers from spending and lenders from lending. The economy, after all, is a confidence game. That's why financial analysts use psychological phrases like "jittery markets" and "economic anxiety." It's no accident that the word credit comes from the Latin word for belief.

"Ben understood more clearly than anyone how a crisis of confidence can create a domino effect," says Liaquat Ahamed, author of Lords of Finance, a vivid history of the misguided central bankers who produced the Depression. It's one of Bernanke's favorite books, except that he wishes he had written it himself; he was working on a similar history for Princeton University Press before he was summoned to Washington in 2002.

His working title was The Age of Delusion.