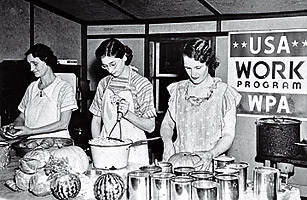

Women work at the Newport Canning Project, part of the WPA program, May 17, 1939.

Seventy-five years ago, Harold Ickes tried to explain to a New York City audience the special bond between the President and the American people. Franklin Roosevelt, the Secretary of the Interior said, was "the leader you have been looking for — for more years than you would like to remember." This was a President, Ickes told the crowd, who would fight for America's forgotten man — the hungry, the senior citizens, the laborers — even as he waged a wider offensive against the Depression.

As it turned out, F.D.R.'s tenacity did not suffice to get the economy back to where it had been before the Great Depression began, in 1929. Today we know that actions Roosevelt took to resolve the crisis may actually have perpetuated it. Especially during the period from 1935 to about 1939, Roosevelt's moves kept recovery at bay.

The first bleak years of the Depression were no fault of his. After the historic market crash of 1929, his predecessor, Herbert Hoover, through a misguided sense of charity, took steps that kept the economy down. By insisting that companies continue to pay high wages at a time when they could ill afford it, Hoover made employers slow to rehire. He signed into law a tariff, Smoot-Hawley, that set off a global trade war. He also joined Congress in pushing the top income tax rate from 25% to a confiscatory 63%.

Meanwhile, events abroad triggered further damage. In 1931, while Roosevelt was still governor of New York, Britain shocked the U.S. by going off the gold standard, meaning that Britons could no longer demand gold in exchange for paper currency at their banks. Foreign governments and individuals then rushed to redeem their dollars for gold. A banking panic ensued. To lure back cash, the Fed pushed up interest rates. Such actions worked to cause a whole new round of bank failures.

In 1932, the year Roosevelt was elected to his first term, 24% of U.S. workers were jobless. As soon as he took office, in March 1933, Roosevelt made a number of positive moves. Brushing aside opposition from the financial glitterati, he created federal deposit insurance for banks. Knowing that they could retrieve their money even if the local thrift closed its doors so reassured small depositors that they were willing once again to leave their cash in banks. The following year, F.D.R. established the Securities and Exchange Commission, which, over the long run, bolstered U.S. competitiveness by promising clear rules for investors in American equities.

Roosevelt also reassured seniors by creating Social Security. During his first term, the stock market rallied strongly, affording snapshots of robust growth for short periods. By the fall of 1936, when he was running for re-election, unemployment had dropped to about 10%, from 20%. Perhaps the Depression was history. Voters rewarded the President with a stunning electoral sweep — 46 of the 48 states.

But at least five New Deal policies would halt that tentative recovery. The trouble started with Roosevelt's erratic budgetary-spending patterns. During his first term and especially in the lead-up to his 1936 re-election campaign, F.D.R. submitted budgets to Congress that called for unprecedented spending. From 1933 to 1936, the federal budget rose from 6% to 9% of the nation's GDP.

Roosevelt's Public Works Administration had such a large budget, $3.3 billion, that even Ickes, who headed it, was astounded. "[If] we had it all in currency and should load it into trucks," Ickes wrote, "we could set out with it from Washington for the Pacific Coast, shovel off one million dollars at every milepost and still have enough left to build a fleet of battleships."