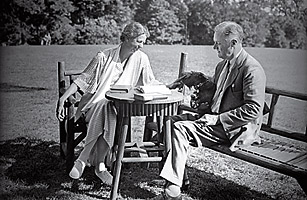

Eleanor and Franklin relax at home in Hyde Park, N.Y., in August 1933. She preferred her retreat at nearby Val-Kill.

When Eleanor Roosevelt learned that her husband was going to run for President in 1932, she fell into a deep depression. "I knew what traditionally would lie before me," she said later, "and I cannot say I was pleased." Eleanor was not First Lady material; of this she was certain. She'd barely survived the agony of her own debutante ball at the Waldorf-Astoria in New York City 30 years before. She felt self-conscious about her buckteeth and her quavering voice. She laughed at inappropriate times. She had no patience for banter.

Now in middle age, Eleanor had finally built a life that fit her — filled with teaching, traveling and talking with friends. It was a constellation revolving near but not around her husband, the governor of New York. She dreaded the idea of giving up everything for a ceremonial life in Washington. On the eve of Franklin's nomination, Eleanor wrote a letter to a confidante, explaining how the White House would suffocate her. A friend, worried that the letter might come back to haunt her, tore it into tiny pieces. That would turn out to be exactly the right metaphor.

Forget First Lady; Eleanor Roosevelt was one of the master politicians of the 20th century, period. F.D.R.'s legacy cannot be understood apart from hers. While some First Ladies are remembered for redecorating the White House, Eleanor was the first to hold press conferences (more than 300 of them), to visit — alone — U.S. soldiers at war overseas and to shrewdly maneuver her agenda through the back corridors of the White House for 12 years, chipping away at segregation, poverty and injustice. She may be the only First Lady ever to have had a Ku Klux Klan bounty on her head.

How did she do it? Modern First Ladies would recognize almost nothing about Eleanor's life. She declined Secret Service protection and carried her own gun (and permit) when necessary. She kept an apartment in New York City's Greenwich Village — in a house owned by a lesbian couple with whom she was good friends — and spent much of her time there when her husband was President.

Eleanor enjoyed tremendous influence largely because she lived a double life — playing gracious First Lady in public and relentless power broker off camera. "She lied," says historian Allida Black, the author of four books about Eleanor. "She covered her tracks with the efficiency of a CIA agent." Eleanor insisted she did not shape F.D.R.'s policy; she was merely a "spur," if anything. She was a master of self-deprecation.

In 1940 her husband was looking to run for a third term, but he was reluctant to personally ask for something so brazen. So he asked Eleanor to go to the nominating convention in his stead. She recoiled at the idea. Never before had a First Lady spoken to a convention, and she worried that she would be seen as meddling. According to Doris Kearns Goodwin in No Ordinary Time, she responded to the idea by telling Franklin, "No, I wouldn't like to go! I'm very busy and I wouldn't like to go at all." But Franklin knew how to appeal to her sense of duty. "Well, they seem to think it might be well if you came out," he said. "Perhaps it would be a good idea." Eleanor boarded a plane to Chicago.

When she arrived, the crowd was belligerent; the delegates perceived the President's absence as a slight. But when Eleanor got up to speak, she did what she was best at: she appealed to conscience. "This is no ordinary time," she said. "No time for weighing anything except what we can best do for the country as a whole." The applause was overwhelming, and the delegates supported F.D.R.'s ticket.