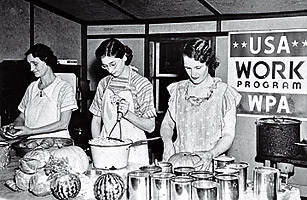

Women work at the Newport Canning Project, part of the WPA program, May 17, 1939.

(2 of 2)

Once safely past the '36 election, the President permitted himself the luxury of second thoughts about outlays. Soon after, he, the Federal Reserve and the Treasury tightened money. Those moves helped cause the infamous Depression Within the Depression, a sharp downturn in 1937 and 1938. As much as the measures themselves, Washington's inconsistencies did damage.

Next came taxes. Instead of reversing Hoover's tax-hike error, Roosevelt compounded it by raising taxes again and again. His Treasury also cobbled together new business taxes. The same caution that had led banks to accumulate reserves during the worst of the downturn had moved corporations to put aside extra cash instead of using it to expand. Roosevelt, angered that firms were not spending to stimulate the economy, retaliated with an undistributed-profits tax on top of ordinary corporate taxes. Taken aback, observers accused him of "breaking the nest egg."

Beyond tax rates, a broader New Deal tax philosophy took its toll. Tax authorities had once drawn a clear line between tax avoidance — the use of legal deductions — and criminal tax evasion. Roosevelt blithely blotted out that line, conflating evasion with avoidance. Anyone who seemed to pay too little became a target of F.D.R.'s prosecutors. One of those targets was Andrew Mellon, Treasury Secretary under Warren Harding and Hoover. Roosevelt's Treasury Secretary, Henry Morgenthau, told prosecutor Robert Jackson, a future Roosevelt appointee to the Supreme Court, that when it came to Mellon, "you can't be too tough."

New Deal labor policy also prolonged the Depression. The centerpiece of the New Deal, the National Recovery Administration, supported minimum wages that employers often could not pay. The 1935 Wagner Act gave John Lewis and what would become his Congress of Industrial Organizations the power to insist that wages stay high or rise while the economy was still fragile. In the late '30s, joblessness rose yet again, and it became clear that double-digit unemployment would be the rule for the decade. People began to realize that the government-jobs programs that Roosevelt had created did not amount to true recovery because those jobs disappeared when the government stopped funding them.

Most intimidating of all was not a fact but a prospect: What more might this President do as he aggregated authority? In his 1937 Inaugural Address, F.D.R. told the nation outright that government was now fashioning itself into an "instrument of unimagined power." This shocked many who recalled the days of smaller government. That same year, when he sought to pack the Supreme Court, it became clear that F.D.R. meant what he said. The bill to allow court-packing was defeated, but voters still wondered where Roosevelt would turn next.

During the Depression Within the Depression, industrial production collapsed and families hungered again. Businesses went on "capital strike," choosing not to invest in the future. Even British economist John Maynard Keynes, who believed in deficit spending, chastised the U.S. President. "It is a mistake to think businessmen are more immoral than politicians."

In those later years of the 1930s, the Dow gave up its previous gains, closing off hope that it would soon return to its 1929 benchmark level. (The market would not regain those heights until the mid-1950s.) Per capita GDP reached pre-Crash levels only at the very end of the 1930s. But worst of all was the abiding unemployment, which gave the Depression its adjective — Great — in American memory.

Astonished by the difficulty of attaining true recovery, Americans talked about how the term forgotten man could have several meanings — it could also describe the citizens who paid for the New Deal. "Who is the forgotten man in Muncie?" asked an editorialist from the Indiana town's paper. "I know him as intimately as I know my own undershirt. He is the fellow that is trying to get along without public relief ... In the meantime the taxpayers go on supporting many that would not work if they had jobs."

When the recovery came, as the decade closed, what were the causes? For one thing, as scholars like Christina Romer, chairwoman of President Obama's Council of Economic Advisers, have noted, gold flowing in from troubled Europe gave U.S. banks the kind of reserves that enabled them to lend more. And as F.D.R. turned his attentions to crises in Asia and Europe, he tired of his war on business at home. Instead of getting pounded, big companies found themselves working hand in glove with the government to arm the U.S. or supply matériel for lend-lease.

The real question about the Great Depression is not how or whether World War II ended it, but rather why the Depression lasted until the war. That episode of American life reminds us that even the best-intentioned government intervention can make things worse. And that when a politician remembers one forgotten man, he often creates another.

Shlaes is a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and the author of The Forgotten Man: A New History of the Great Depression. She is currently writing a biography of Calvin Coolidge