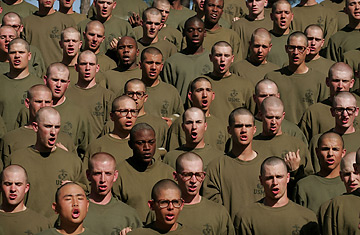

Marine Corps recruits.

Soldiers hate friendly fire, especially when it comes from the White House. Yet that's just what happened late Friday, August 10, when Army Lieutenant General Douglas Lute, President Bush's deputy national security adviser for Iraq and Afghanistan, suggested it was time for the nation to consider resuming the draft. "It makes sense to certainly consider it," he told National Public Radio. The counterattack was intense. "There is absolutely no consideration being given to reinstituting a draft," Pentagon spokesman Bryan Whitman said early the following Monday morning. General George Casey, the Army's top officer, also tossed a grenade Lute's way, 24 hours after Whitman, during an appearance at the National Press Club. While conceding today's Army is "out of balance" — making the woes afflicting the world's most potent fighting force sound like a wobbly Firestone 500 —Casey too tried to extinguish such talk. "Right now there is absolutely no consideration — at least within the Army — being given to reinstituting the draft," he said.

Casey's qualification — "at least within the Army" — is significant. For while his view is shared by Robert Gates, the current defense secretary, it runs counter to the recommendation of the first Secretary Gates. At his confirmation hearing last December, Bob Gates called the Army's personnel woes "a transitory problem" that didn't warrant renewed conscription. Yet Thomas Gates, who served as defense secretary from 1959 to 1961, chaired a commission created by President Nixon in 1970 to consider doing away with the draft. While the panel recommended doing away with conscription — just as Nixon wanted — it also called on the nation to maintain a "standby draft" that would resume if there were "an emergency requiring a major increase in force over an extended period," which certainly fits today's sitrep. The commission pointedly noted that the draft's resurrection should be ordered by Congress, and not the President. "If a consensus sufficient to induce Congress to activate the draft cannot be mustered," it said, "the President would see the depth of national division before, rather than after, committing U.S. military power."

Yet since the draft's end in 1973, it has become obvious that the nation has little stomach for its resumption, even as part of a bigger package mandating national service. While some military experts — including those who have worn the uniform — think national service, with a military option, makes sense, more are opposed to the notion. But it's also plain that the U.S. military's increasing isolation from U.S. society is not a good thing.

Those who favor national service, including a military element, argue that it is a simple responsibility of citizenship that young people should incur in exchange for the fortune of being an American. George Washington and the 1918 Supreme Court embraced this view. Today's backers say it would help knit the various cliques of the nation together, they maintain, and help deal with a wide variety of problems — a lack of soldiers and inner-city teachers among them — at the same time.

Opponents — among them Ronald Reagan and economist Milton Friedman —have maintained that such mandatory service has no place in the democracy. Many experts say that the sharp edge of today's volunteer military, honed over 35 years after initial opposition from the Pentagon, can only be dulled by adding draftees to the force. Most agree that any military obligation could be made more palatable if it were part of a bigger national-service program. Ideally, that would mean that even those fulfilling their national-service obligation by enlisting would do so, at least to some degree, voluntarily (because they could always have opted to have fulfilled that requirement by serving in some non-military slot).

But much of this debate remains fuzzy: if there were a national-service requirement, might some be forced into the military against their will if all the civilian options were already filled? The Air Force, Marines and Navy haven't had much trouble filling their ranks, so would draftees all be funneled into the Army — and more specifically, into the blood-and-mud ground combat units? Beyond such concerns, military officers say, there plainly aren't sufficient jobs — or sufficient money — to employ the entire cohort (as of July 1, there were 4.3 million American 18-year-olds, and 4.4 million American 17-year-olds, according to the Census Bureau). So just as draft deferments poisoned the Vietnam-era draft, how would a new national-service program fairly choose among those eligible (the draft lottery, used for awhile at the end of the Vietnam war to select those who had to serve, has been replaced by state lotteries seeking to fund social programs on the backs of those least able to afford it. Perhaps it could be brought back to life, along with the draft). Would women be included, or exempt? Why include them when current law bars them from the combat forces most in need of personnel?

Charles Moskos, the nation's pre-eminent military sociologist and a long-time professor at Northwestern University, has supported national service, including a military option, for the past half-century. "My drafted contemporary was Elvis Presley — just imagine how it would be if Justin Timberlake were serving today," he says. "I addressed a group of recruiters last year and I asked them if they'd prefer to have their advertising budget tripled or have Jenna Bush join the Army. They unanimously chose the Jenna option. If you get privileged youth serving," he adds, "it makes recruiting a lot easier." Moskos, who has spent decades visiting U.S. troops in various hotspots around the globe, likes to speak of his alma mater to show how times have changed. "In my Princeton class of 1956, out of 750 males, some 450 served, including Pete Du Pont and Johnny Apple," he says. "Last June's graduates — out of a class of 1,100, both men and women now — nine are serving."