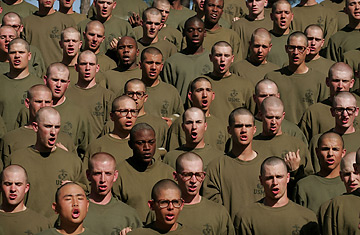

Marine Corps recruits.

(3 of 3)

While most civilian military experts interviewed support the idea of national service, including the military, most retired military officers are on the other side of the argument. (It's worth noting here that the military opposed ending the draft a generation ago, so their opposition needs to be taken with a grain of salt.) They argue that when the draft was last used, the military was largely a low-tech enterprise. But now the inside of an M-1 tank looks more like the bridge of the Starship Enterprise, and takes substantial training to operate effectively. The cost of such training would skyrocket if draftee soldiers had to serve only two-year hitches, meaning greater numbers would have to be trained because of their shorter time in uniform. Even more critical, veterans say, is the ethos of the all-volunteer force, which is difficult to measure but impossible to ignore.

National service "is an absolutely bad idea," says Barry McCaffrey, a retired four-star Army general. "My age group learned to love the volunteer military." While McCaffrey says the idea of national service "makes sense in a civic sense" it would lead to lesser-quality soldiers. "We've never had better soldiers in the country's history" than we do now. "They volunteer for the Army, volunteer for combat units, they're high school graduates without felonies, they stay longer," he says, rattling off attributes he fears would shrink with national service.

Robert Scales, a retired Army major general, is an Army historian who once commanded the Army War College. "War has become so complex, and so dependent on ground forces, that the idea of drafting soldiers would greatly harm the American military," he says. "First of all, they wouldnt go into the military goddammit — they'd go into the Army. And if they go into the Army, they're going to go into the combat ops" — infantry, armor, artillery — "because those are the jobs that nobody wants." To Scales, the paradox of resuming any kind of draft is that it would fill those ranks with people who do not want to be there, just as those ranks have become increasingly important. "The critical job in today's military — the jobs that have to be done right — are those close-combat jobs," he says. "So the irony is that in a draft those skills and will and morale and physical fitness — all those things that we most need in the close combat arms — are least likely to be attained."

John Keane, the Army's former No. 2 general, differs slightly from his colleagues. He is willing to entertain the idea of national service, including the military, so long as no one is forced to serve in uniform against his or her will. "National service is a good idea so long as the military, which would be the most demanding of the national service options, has to stay completely voluntary," he says. "We wouldn't want anybody in it who didn't want to be in it. I think that is a compromise that we in the military should be willing to make for the betterment of the country." Keane says today's youngsters are yearning to serve. "I've been dealing with this age group — from 17 to 25 — for most of my adult life," he says. "The current group of young people, particularly in the post 9/11-era, have a sense of purpose about them — they want to do something with their lives. It's not just in terms of 'What's good for me?'

Keane says that while such service "would be only for a very short period of time, I think the experience and satisfaction of it would actually last a lifetime." And he doesn't think it would harm the Army. "When you have volunteers, you can demand so much more of them," he says. "I'd like to think that the people who would still join us under a national-service requirement would really want to be a part of it. While some of them would be a little more challenging than the volunteers we have today, I would like to think that it would not diminish the Army." And there would be an added benefit. "With the professionalization of the Army, we have a tendency to be considerably more isolated from the American people," Keane says. "In terms of the health of the nation, and even of the institution itself called the U.S. military, the fact that more people would be connected to it through some form of national service would be very healthy."

Today's military was built to fight Colin Powell's kind of war — brief and intense — like the 1991 Gulf War. The U.S. military really doesn't have the depth to wage a sustained ground campaign as we are now doing in Iraq, many military officers say. If the U.S. thinks its future will consist of drawn-out campaigns like that now underway in Iraq, the prospect of a draft makes more sense. While the 1.4 million-strong U.S. military (with another 1 million reservists) is at the breaking point with only 162,000 troops in Iraq, that total is well below what experts estimated would be needed to tame that country. The Rand Corp. said in 2003 that, based on historical troop-to-population ratios from prior wars, the number of troops needed in Iraq would range from 258,000 (based on Bosnia) to 321,000 (based on post-World War II Germany) to 528,000 (based on Kosovo). The numbers suggest that if the U.S. really believes there is a war on terror to be won — and, if as the Bush Administration keeps saying, it is going to be a long war — more troops are going to be required to wage it.

Indeed, the all-volunteer force is getting expensive. The Congressional Budget Office reported in June that a string of pay raises and benefit hikes have led to a 21 percent pay hike over the past six years for enlisted troops. The bottom line, according to the CBO: the average soldier is better paid than the average civilian. While such comparisons are difficult to make, the CBO reported that enlisted military personnel are paid at a rate equal to the 75th percentile of private-sector workers with similar education. (For those whose math skills have deteriorated, that means that those wearing the nations uniform are paid more than 75 percent of their civilian counterparts.) The Pentagon, in recent years, has tried to peg its salaries for enlisted folks at the 70th percentile. Too often, Pentagon officials say, comparisons of military pay only measure paychecks, which shortchanges military people who receive many valuable benefits — largely tax-free food and housing allowances — that civilians don't.

In a second report released August 15, the CBO noted that total pay for a starting soldier is $54,900 when allowances and bonuses are included. "We're getting a little too heavy on having a professional Army — the bills that are going to be coming due for retirement and medical care are going to be horrendous," Moskos says. "We're ending up with overpaid recruits and underpaid sergeants — in the old days a master sergeant with 20 years' experience made about six times what a private did — now it's about 2.5 to 1." Rangel agrees. "In terms of military volunteers, a lot of money is put into that to pump up patriotism — I mean $20,000, $30,000, $40,000 in enlistment and retention bonuses," he says. Of course, the true cost of renewing the draft — for good and for ill — could go well beyond figures punched into Pentagon calculators.