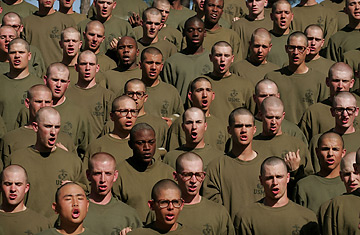

Marine Corps recruits.

(2 of 3)

Rep. Charles Rangel, a New York Democrat, has pushed unsuccessfully since 2002 for a wartime-only draft. The Korean War veteran (he served in the Army from 1948 to 1952) and Bronze Star and Purple Heart winner unabashedly declares that his legislation would reduce the number of wars the nation fights. But he also adds that it would inspire a greater sense of citizenship among young people. "Shouldn't young Americans be given an opportunity to know and serve their country for two years?" he asks, recalling his own service. "There was something about that flag, something about the march, something about the music," he said in an interview with Time. "I know every son-of-a-bitch who got out with me felt patriotic."

Many in the military brush off Rangel's call because they think it is more of an anti-war proposal cloaked in civic-responsibility garb. They particularly disliked his original claim that minorities are over-represented in the all-volunteer military (after it became clear that was not the case, Rangel shifted his argument to focus on how the military's current makeup allegedly relies heavily on the poor. In a June report, the Congressional Budget Office said the scant available data on socio-economic status of the families of military members "suggest that individuals from all income groups are represented roughly proportionately in the enlisted ranks of the AVF.")

Now chairman of the ways and means committee, Rangel unveiled a retooled version of his original bill — which lost in the full House, 402-to-2 shortly before the 2004 election — in January. "My bill requires that, during wartime, all legal residents of the U.S. between the ages of 18 and 42 would be subject to a military draft, with the number determined by the President," he said then. "No deferments would be allowed beyond the completion of high school, up to age 20, except for conscientious objectors or those with health problems. A permanent provision of the bill mandates that those not needed by the military be required to perform two years of civilian service in our sea and airports, schools, hospitals, and other facilities."

Rangel says the civilian national service requirement would continue during peacetime under his proposal. "I know that if we had those people at Katrina their presence would have given so much hope to that community," he said in an August 24 interview. "If you went to the airports, they don't need guns — all they need is that (flag) patch (on their shoulder) and knowing that our country is there. The same in the train stations, school rooms and hospitals — there's so much that young people can do."

He says his bill would make the U.S. less tilted toward war. "We never would have gone to war" in Iraq if legislation like his had been on the books, Rangel says. "I go to Wall Street for the last five years for one reason or the other. I'm in front of every Business Roundtable, the U.S. Chamber, and members of Congress and there's one question: if you knew at the time the President said he was going to invade Iraq, and there was a draft and your kids and grandkids would be vulnerable, would you support the President? And no honest son-of-a-bitch has ever told me 'yes' — never," Rangel says. "When some of them mumble that, and their wives are there, I just look at the wives and they grab their husband's hand and say 'No, we would not support it.' If going to war meant talking about sending my kid, the answer would be 'Hell no, let's talk this over, let's wait awhile, let the UN come in, let's see where France is, I mean, let's see where the world is before you grab my kid."

But if war did come, under Rangel's bill some young men and women would be forced to serve in uniform against their will if the military needed their bodies. "Mine is no exceptions, no exclusions, nobody's deferred" except for reasons of health or conscientious-objector status, Rangel says. "Under my bill, there are nine chances out of 10 your kid wouldnt go, but goddam he'd be required to be eligible to go if he was drafted, and thats the part that sticks in the craw of most members of Congress," Rangel says. "You take your chances — for every guy who gets killed, there's a hundred guys who don't come anywhere near the guy who gets killed — so your chances of getting shot are slim, but they're real."

Moskos, like Rangel, likens his military tenure — he was a draftee in the U.S. Army, 1956-58 — as a personally profound rite of passage that the nation's youth (at least the males) no longer experiences. "There was a genuine mixing of all social groups, by race, region, education, social status," the proud Greek-American says. "When I talk to veterans today of any era, it's like talking to a fellow ethnic." He advocates a broad form of national service, where the military would just be one option among many. "Two-year draftees could well perform missions like border guards, peacekeeping, guards for nuclear and physical plants," he says. "Even many of the jobs on forward operating bases in Iraq could be well performed by draftees."

Moskos says there is a sense of selfishness afoot in the country today. "This is the first war in American history where no sacrifice of any kind is being asked of our citizenry," he says. "And the soldiers in Operation Iraqi Freedom know this — 'patriotism lite' is the ethos of the day." That can be seen, he says, in our national politics. "In the last four presidential elections, the American public has voted for the draft dodger over the server," Moskos says, slighting the current President's controversial tenure in the Texas Air National Guard. "Contrary to conventional wisdom, being a military veteran is not a political advantage. It would be with the draft back in play." Moskos, like Rangel, believes that having a cross-section of the nation's youth serving in uniform means the nation would be less-inclined to go to war. "If you have privileged youth serving, going to war is much more debated, and you're much less likely to go in," he says. "But if privileged youth are in there, once you go to war, you're much more likely to hang in there."

Lawrence Korb, who served as the Pentagon's personnel chief during the Reagan administration, also endorses the idea. "National service is great — I think everyone ought to do something for their country," he says. But he adds it shouldn't be thought of as a fix for the military. "The all-volunteer force is not in trouble — the all-volunteer Army is in trouble," he says. And he doesn't embrace Moskos' notion that salting the force with draftees would make going to war more difficult. "If there had been national service, including the Army, on the eve of the war —remember, on the eve of the war, 60 percent of the American people thought Saddam had weapons of mass destruction." If military service is merely one option among many for national service, Korb isn't convinced it would affect what wars the nation chooses to fight. "The only thing that acts as a brake is when you force people to go into the military," says Korb, a Navy veteran, "particularly the ground forces."

David Segal, another prominent military sociologist, also thinks national service would be a good idea for the country. "The military is opposed to a broad national service system because they assume that they would get the short end of the stick," says Segal, director of the University of Maryland's Center for Research on Military Organization. Pentagon complaints that draftees would dull the military's fighting prowess are bogus, he says. "The distinction we make between combat and combat support doesn't reflect the realities of 21st Century warfare," he says. "We're sending individuals from the Air Force and the Navy to be soldiers." Segal says it is "political suicide" to advocate for a draft amid a war, but says a program of national service would have a better chance because of its non-military options. He argues that it should not be compulsory, but strongly encouraged: college loans and grants might be contingent upon such services, as would public employment and maybe even drivers' licenses. "It should be as minimally coercive as possible," Segal says. "You need to reward it with a carrot rather than punishing non-compliance with a stick."