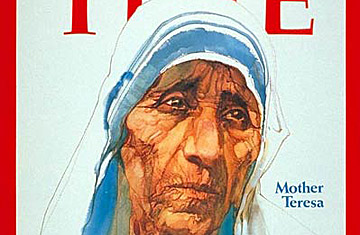

Mother Teresa

(8 of 10)

What Gmeiner has done for orphans, Canadian Jean Vanier has accomplished in a similar way for mentally retarded adults: permanent and caring communities. A Catholic layman and son of a former Governor General of Canada, Vanier spent 14 years of spiritual search before moving into a dilapidated old house in Trosly, France, in 1964 to share his life with two retarded men. Since then, L 'Arche (the Ark) communities, in which the normal and retarded share a common life, have opened on four continents. Vanier describes the homes as places of "human and spiritual progress," where the retarded gain in hope and confidence while the more fortunate who come in contact with them are drawn toward a life of simplicity and self-giving.

The call to help can come fairly late and in strange places.

Denny and Jeanne Grindall, Presbyterians from Seattle, where Denny is a florist and nurseryman, found their call in their 50s on a 1968 vacation in Africa. Visiting some Masai nomads in Kenya, they were appalled at the disease, drought and hunger. "We knew what we had to do," says Denny Grindall. "God led us to this place." He studied up on engineering and put his new learning to work (along with quiet infusions of the family savings) in a succession of six-month stays in Kenya. The Grindalls have won the respect and affection of the Masai and changed their way of life. The once nomadic tribesmen, guided by Denny and Jeanne, now till vegetable farms around a new self-built dam; Jeanne also teaches the women nutrition, hygiene and how to make clothes. The Grindalls' philosophy is simple: "Individuals have a responsibility to the Lord to use any brain and muscle that He has given us to help others."

To many religious people, good works are not enough in the face of the world's cruel inequities. They seek social solutions. Tanzanian Bishop Christopher Mwoleka, a black and a Catholic, sees a solution and basic Christian value in the ujamaa cooperative villages. A member of the Nyabihanga ujamaa village in his diocese, Bishop Mwoleka spends two weeks of each month at work in the fields, barefoot and clad in tattered shirt and dungarees. He argues that the cooperative way "is a practical way to imitate the life of the Trinity, a life of sharing."

In the U.S. one widely acclaimed spiritual heroine feeds the poor and campaigns fiercely for a better world. She is Dorothy Day, the snow-haired philosopher-founder of the Catholic Worker Movement and still its indefatigable voice. She has been jailed eight times—most recently as an illegal picketer for Cesar Chavez's United Farm Workers in 1973. (Many regard Chavez himself as a saint for his selfless, intensely spiritual devotion to his cause.) A Marxist in the '20s, she bore a daughter to her common-law husband, but became a celibate after converting to Catholicism. "The best thing to do with the best things in life," she says, "is to give them up."