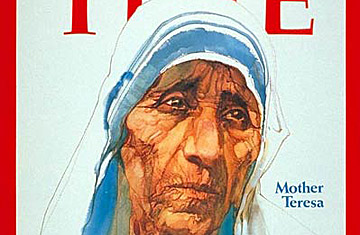

Mother Teresa

(3 of 10)

Jews do not talk of saints, but prize the zaddik, the "righteous person." A zaddik, explains Orthodox Rabbi Stephen Riskin of Manhattan's Lincoln Square Synagogue, is "deeply pious, self-effacing, generous with everything he has, burning with a desire to serve God and serve mankind. One serves God by serving man, and man by serving God. The two are intertwined." Besides recognized zaddikim, there are according to Jewish lore a group of hidden zaddikim in every generation, believed to number at least 36, upon whose merit the existence of the world depends. Only the virtue of these 36 hidden saints—lamed-vovniks in Yiddish—stays God's hand from destroying the world.

Do the old saintly qualities still apply? Australian Anglican Ross Walker, a social worker in Canberra, says they have not changed much since Jesus' time: "Love, self-denial, continuing self-sacrifice and grace are all necessary." Though saints "like to keep what they do private," he says, their very personalities often betray them: "They are all inspiring, larger-than-life people."

Austrian Catholic Theologian Adolf Holl also believes that the essentials the church sought in saints have not altered. The saint must exhibit a heroic degree of virtue akin to the asceticism that ancient athletes and warriors strove to perfect. And the works of a saint must be out of the ordinary, almost unique. He or she should have a charisma or aura, the kind of radiance that was classically symbolized by a halo. The life of a saint should display a certain personal serenity.

Saints normally are not normal. "A saint has to be a misfit," says University of Chicago Church Historian Martin Marty. "A person who embodies what his culture considers typical or normal cannot be exemplary." Father Carroll Stuhmueller of Chicago's Catholic Theological Union agrees. "Saints tend to be on the outer edge, where the maniacs, the idiots and the geniuses are. They break the mold." Not all accept that description of a saint. Hewing closer to Protestant tradition. Church Historian Jane Douglas of California's School of Theology at Claremont insists that saints are no more, no less than "Christians who go about their tasks in the world with a kind of holiness that grows out of faith."

Perhaps the best definition of sainthood is one that draws remarkable agreement: the saint as a window through which another world is glimpsed, a person "through whom the light of God shines." It is just that light that many see in Mother Teresa.

The once waspish Malcolm Muggeridge, a recent convert to Christianity, writes movingly in his book Something Beautiful for God of putting her on a train in Calcutta.

"When the train began to move, and I walked away, I felt as though I were leaving behind me all the beauty and all the joy in the universe. Something of God's love has rubbed off on Mother Teresa."